Google's censorship of California journalists is a preview of AI's future

It is time to regulate Big Tech.

It’s kind of like seeing Tom Ripley pull up in his yacht to wrap a plastic bag around the head of a man who’s already drowning. And oh, it was a guy who Ripley had probably thrown into the water in the first place.

This morning’s news that Google ($2 trillion market cap, $20.7 billion in profit last quarter, $48 billion revenue from search) is going to start blocking news stories in California as a political bargaining chip — because it doesn’t want to pay news publishers for journalism in a bill my union supports — wasn’t surprising. But it’s ghastly to see nonetheless.

Look around. Those of us in Los Angeles are watching an utter economic meltdown happening across the local journalism community right now. What’s striking isn’t just its severity but the breadth of the crisis across almost every type of community news organization you could possibly imagine:

The state’s flagship local newsroom, the Los Angeles Times, my longtime home, has shrunk by about 40% since 2019, culminating with massive layoffs last June and this January, featuring major cuts to its forward-thinking audience engagement and visual media teams.

In the public media space, LAist (formerly KPCC) cut more than 10% of its staff in June, followed by similar cutbacks at KCRW.

The Long Beach Post, the principal newsroom for California’s seventh-largest city, went from a staff of 26 in August, converted to a nonprofit, couldn’t secure enough philanthropy, refused to recognize its’ journalists union and laid most of them off, with a remaining editorial staff of maybe three people who remain out on strike.

Knock LA, a progressive local news publication sponsored by the activist group Ground Game L.A.’s 501(c)4, is currently in uproar over its most prominent journalists accusing Ground Game of interfering with their editorial autonomy, not paying freelancers on time and who have gotten kicked out.

L.A. Taco, a beloved independent local digital publication that has been experimenting with new ways to do local journalism and reach long underserved audiences, furloughed its staff this week and said it won’t be able to make payroll unless it can hit 5,000 subscribers by April 26. (SUPPORT L.A. TACO HERE)

A lot of things have been going wrong, but one of the thing that caught my eye in L.A. Taco’s crisis announcement by editor Javier Cabral last night was his note that “Google's A.I. that pulls information for its self-generated responses from news organizations without linking back had something to do with it, too.”

To get to Google’s role in this in a second: What’s so dire to me about each of these crises is that they refute, in the aggregate, a variety of currently popular and feel-good assumptions out in the journalism policy world that maybe we can digitally innovate and philanthropy our way out of the collapse of local journalism.

It’s the digital innovators here in Los Angeles who are suffering the most. The media entities that seem to be suffering the least? The more heavily analog-centered legacy organizations like local commercial T.V. and the poverty-wage-paying Southern California News Group (owned by Alden Global Capital), which seem to have avoided most of the recent bloodletting.

If you go talk to some of the local publishers around town, they will probably tell you that there is not nearly enough philanthropy going around right now, and certainly less than they’re hoping for — in one of the wealthiest cities in America.

I will offer the suggestion to you that maybe the digital infrastructure company with the $2 trillion market cap, $20.7 billion in profit last quarter, $48 billion revenue from search, is more malefactor than bystander here.

Here is how Google apparently views the future of journalism, per a recent op-ed in the Washington Post by Jim Albrecht, the senior director of news ecosystem products at Google from 2017 to 2023:

In the print era, publishers created “articles,” printed them on paper and distributed that paper to their readers. The web changed everything about the distribution and the literal paper, while the articles remained mostly untouched. But in the future, publishers will have to think less about those articles and more about conversations with users. The users will interact less and less with the actual articles and instead talk about the articles with what the tech industry used to call “intelligent agents.”

… The new breed of LLM-powered Clippy is going to do all the things Microsoft hoped it would in 1996: brief you on the news, your day, your emails; respond for you; answer your questions; help with your work. One morning, it might let you know that “The Washington Post announced it has launched a new AI assistant, called Marty.” As you ask for more info, it says, “Why don’t I just ask him to join us right now since you’re a subscriber.” Marty joins the conversation and gives you a roundup of The Post’s latest coverage, responds to a question you have with a relevant info graphic, updates you on some political gossip and recommends a newly reviewed TV series based on your interests. (Because you’re a subscriber, he knows what you like.) “Can you find me a restaurant for Thursday night?” you ask, and Marty gives you some of the best local options and what they’re known for, and he notes that he can offer you a discount at one of them. Maybe you decide to make Marty a part of your daily briefing or, on the other hand, maybe you turn to your ChatGPT agent and ask, “So what do I need you for?” She might say, “I can do things like make travel arrangements,” to which Marty responds, “We have a travel agent we work with, as well. Shall I ask ExpediaBot to join?” Welcome to your new daily newspaper.

Was I the only person who read all this who noticed that Google’s idea of the future of journalism does not seem to involve any journalists?

When Google says this morning that it’s going to experiment with banning California journalism — brazen retaliation against the big news publishers pushing to regulate Google, but also to scare the shit out of smaller publishers and try to pit them against their fellow journalists — one of the reasons I found it so grim is that this bargaining tactic is actually a pretty good preview of the AI-driven future of journalism that Google is already aiming at.

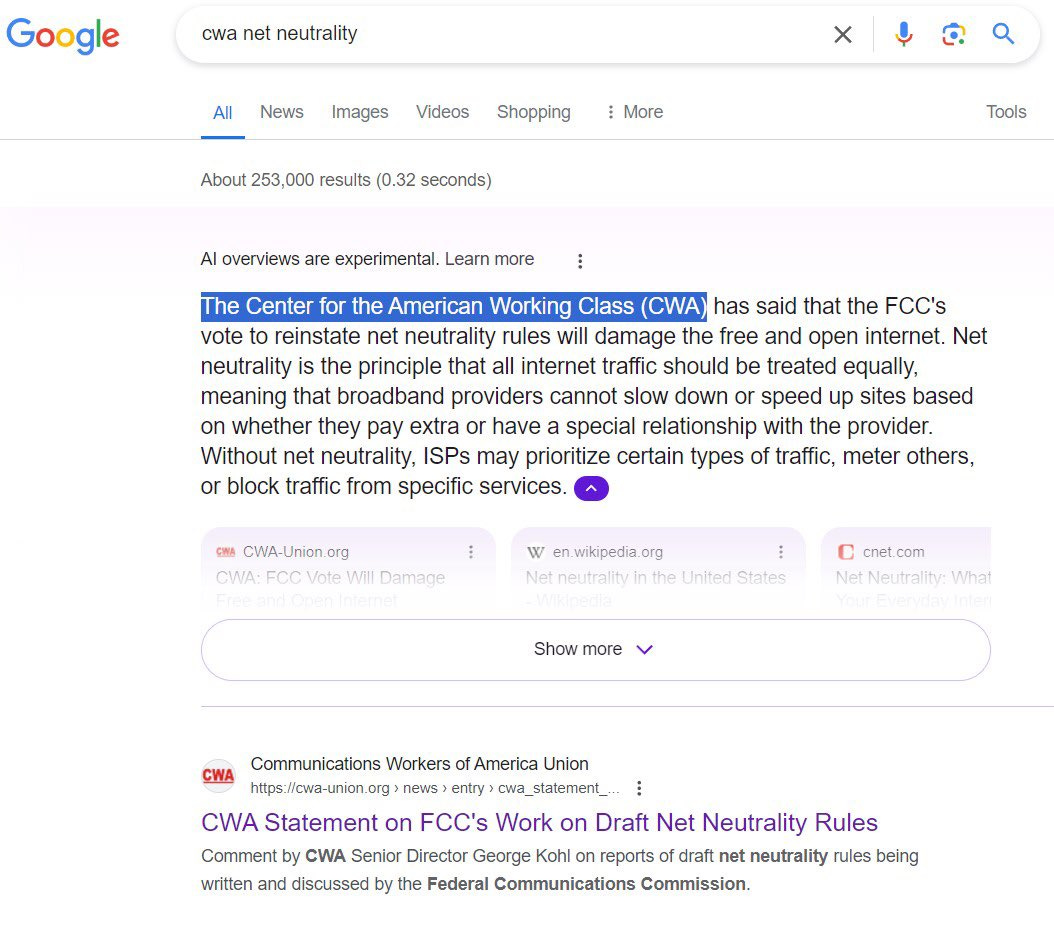

Look: The other day I used Google search because I wanted to look up the past positions of my parent union, the Communications Workers of America, on net neutrality. Here’s what Google’s experimental AI spit back at me:

I mean, I laughed at the time, because the Google AI’s output was so brazenly awful and untrustworthy.

But look at how the AI output, scraped from journalists, Wikipedia editors and CWA itself, presents the information: Links (a huge source of referral traffic for news publishers still) are pushed farther down the landing page. Apparent sources for the summary are hinted at, but slightly concealed.

This is not the UX of a company that’s thinking about more smoothly referring users away from its nascent chatbot-like service. This is a UX that wants to use free labor and free content to keep users’ undivided attention on itself as much as it can. The open internet continues its casino-fication.

The reason Google is retaliating against news publishers today and censoring journalists’ work is because Asm. Buffy Wicks has proposed a bill that would require massively profitable tech companies like Google ($2 trillion market cap, $20.7 billion in profit last quarter, $48 billion revenue from search) to stop stealing our labor and to pay us for our work.

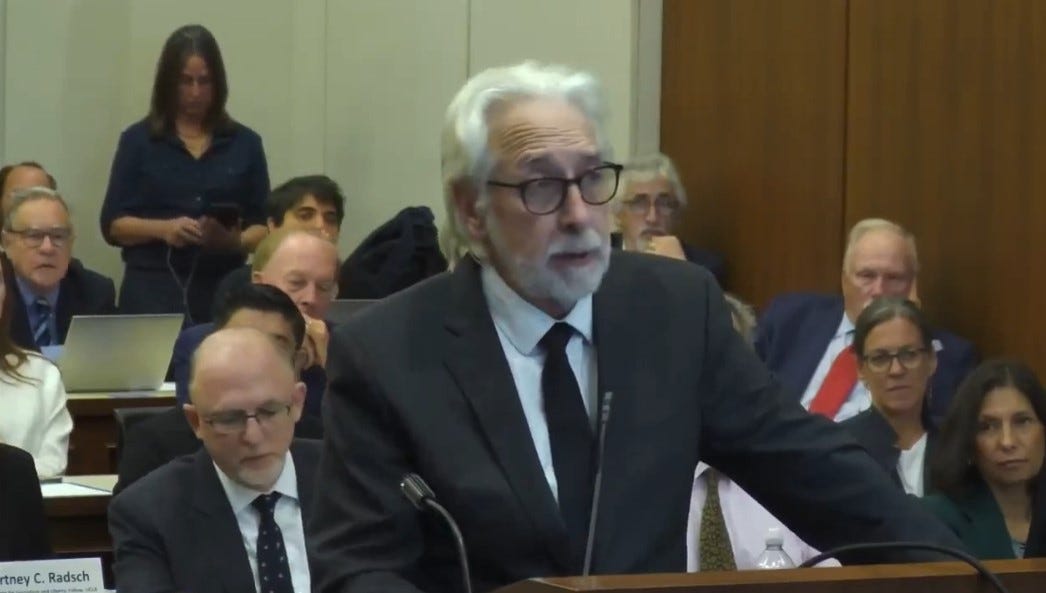

The bill is currently held over and undergoing amendment in the California Senate Judiciary Committee, which invited me to testify on behalf of my union, Media Guild of the West, at an informational hearing in December. I guess it’s relevant today to share this exchange I had with the committee chair, Sen. Tom Umberg:

UMBERG: If we craft something that's particularly onerous, and Google says we think that we don't benefit from this and they pull out, then as I understand it now, in terms of President Pearce, what happens in your world?

PEARCE: Could mean layoffs. And I'm going to say something really controversial here, but since I'm the union, I don't think government officials and policymakers like you should respond to corporate threats in deciding what's good public policy for our democracy.

I meant it then, and I sure as hell mean it now. But someone who apparently didn’t mean what he said at the hearing was Google vice president of news Richard Gingras, who, pretty quickly after hearing me say this, testified to Umberg:

GINGRAS: We have no desire to stop including news in Search.

I remember this because the guy was literally sitting two feet away from me when he said it. But I’d also like to thank my friends working on CalMatters’ handy Digital Democracy project for providing video and transcript of Gingras saying it in case you want to evaluate if Google’s representations to our policymakers about its intentions are being given in good faith. This is an example of the good that tech can do in the hands of working journalists who care about things like what happens in hearings and who says what in their testimony.

But $2 trillion market cap, $20.7 billion in profit last quarter, $48 billion revenue from search. What’s not to love?

Why do you seem to imply that search results summaries should not draw from Wikipedia? Wikipedia content is distributed under CC BY-SA 4.0 copyright license.

I recently switched to Duck Duck Go. I really like it. 😤 Google.