Last week, when I wrote about the urgent need for journalists to contribute to journalism policy debates, I said that having a powerfully funded public media in the U.S. would be amazing but probably wouldn’t happen anytime soon.

A reader (thanks Abby!) asked me why. In a word: politics.

It’s hard to sustain a public option without nonpartisan buy-in. There have been repeated campaigns over the years to strangle the already underfunded Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which gives federal grants to NPR, PBS and your local public broadcaster. These days what we call public media in the U.S. is really nonprofit media with a bit of government support tacked on. CPB grants probably make up less than 15% of your local public broadcaster’s revenues.

It’s easier to defend or expand a popular public option that already exists, like the BBC in Britain or the CBC in Canada, than to create one from scratch (that’s why Medicare for All is called Medicare for All). Congress can barely keep the federal government running as it is.

Hence why I’ve been using my current pulpit as a journalism labor leader to push for broad-based policies like payroll tax credits and interventions regulating how monopolistic tech platforms exploit journalists’ labor. Journalists need help right now, and happily, there’s a window on these sorts of policies to make gains.

But booting up a public option at the local level is something that’s happened before, right here in Los Angeles.

During another troubled moment for American journalism, Los Angeles created its own public newspaper.

I love the Los Angeles Times. It’s not perfect (that’s why we unionized the place in 2018), but its journalists have been a powerful force for the public good for decades. A lot of my interest in the journalism policy space comes from a conviction that newsrooms with this much potential deserve to survive and thrive.

However, the The Times was once not so good, especially before the Otis Chandler revolution turned the place into a Pulitzer factory in the 1960s. As Hendrik Hertzberg recounted of those early years for the New Yorker:

The Los Angeles Times was known for one thing above all: its badness. This badness was of no ordinary kind. The L.A. Times was venal, vicious, stupid, and dull. It was abominably written and poorly edited. It existed to advance the unfathomably reactionary political views of the family that controlled it and, even more, to aggrandize that family's private economic interests. Though it had plenty of money—for nearly the whole of the twentieth century, it carried more advertising than any other paper in the country—its meagre allotment of national and international news was lifted from other papers or pulled lazily from the tickers of the wire services. Its political coverage was propaganda. Its local coverage was a combination of gaseous boosterism and outright suppression of anything that might inconvenience the business community, especially those considerable sectors of it in which the paper's owners had a direct interest. The great S. J. Perelman, in an account of a train trip to California, wrote, "I asked the porter to get me a newspaper and unfortunately the poor man, hard of hearing, brought me the Los Angeles Times."

But during an extraordinary moment of social upheaval in Los Angeles in the early 1900s, Progressive reformers and the labor movement rebelled against the city’s slanted newspapers, including The Times, and pushed for a more civic-minded vision of journalism.

As Robert W. Davenport wrote in the California Historical Society Quarterly:

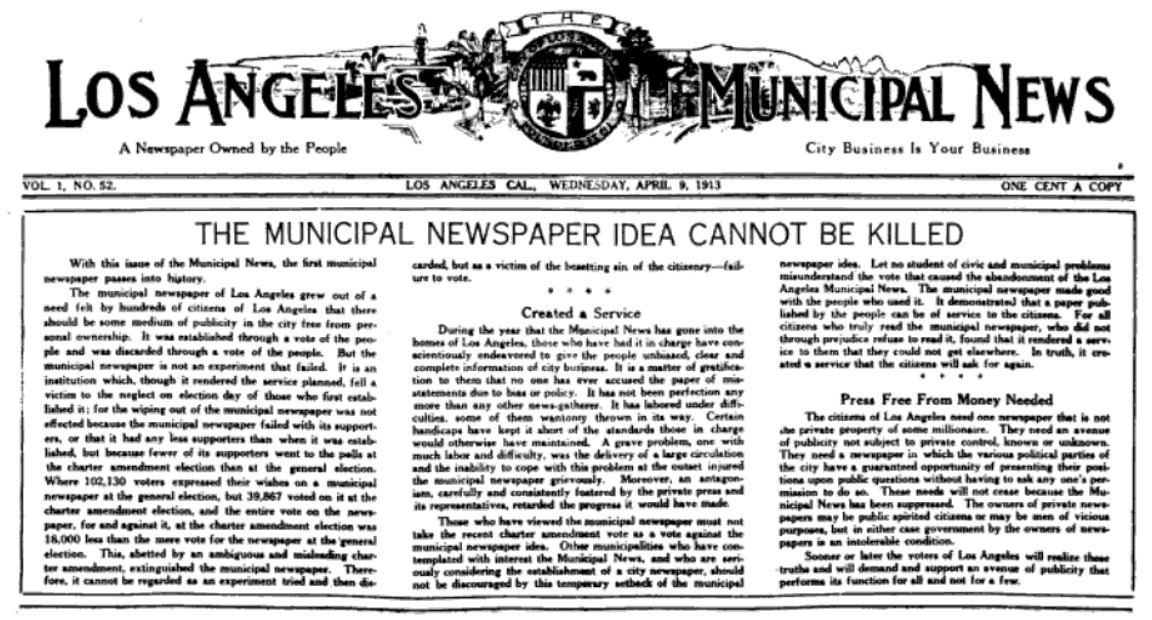

One day in April, 1912, an unusual newspaper appeared on the door steps of thousands of Los Angeles homes. On its logotype it declared that it was "A Newspaper Owned by the People!' On its editorial page the Los Angeles Municipal News proudly announced that it was the first commercial-type newspaper ever published by a city. Unlike its contemporaries, this paper was not private property; it was a public press, voted into being by more than fifty-seven thousand people at the city election in December, 1911. It was a local protest against the excesses of yellow journalism, and its sponsors hoped it would improve the product of the Los Angeles press.

Union carpenter and later L.A. City Council member Fred C. Wheeler, a passionate advocate for public ownership, had persuaded his central labor council (today’s L.A. County Federation of Labor) to lobby for the the Municipal News’ creation, according to historian Jeffrey D. Stansbury’s excellent history of Los Angeles’ labor-driven reform movement between 1900-1915.

George H. Dunlop, the former mayor of Hollywood and a Progressive direct democracy advocate, later persuaded City Council to put the question on the ballot. The initiative laid out some pillars for the new municipal paper:

It should give prominence to municipal matters and not allow them to be side-tracked for the sensations of the day.

It should publish the municipal news accurately, not coloring its news columns with bias of any kind.

It should make ample provision for the publication of the arguments on each side of live public questions.

The function of the paper was to centralize the city’s political arguments into a place where the public could see them. As Dunlop recounted in 1912:

When any municipal question is actively under discussion before the people, that is to say, before the official policy of the city has been determined in the matter, The Los Angeles Municipal News appoints two special writers, each of whom writes a special column — one on each side of the question under discussion — and the two columns are published side by side properly headlined as the arguments for and against. The two special writers, though appointed and paid by the paper, each consult freely with the friends of the side of the controversy which they represent, and in a very large measure present the arguments for that side in accordance with the wishes of the leading proponents thereof. This provision for a hearing for each side of active public questions is one of the most highly appreciated features of the paper.

Each political party, whether national or local, that polls 3 per cent of the vote of the city at any regular election, is allowed the free use of one column in each issue of The Los Angeles Municipal News. In these columns, each carrying appropriate headlines to indicate the respective parties to which they belong, the political parties are allowed to express their positions on public questions in their own way, free from any censorship whatsoever by the management of the paper, excepting that the matter published in the columns must be lawful for publication. The city administration or the newspaper itself may be freely criticized in these party columns. At the present time there are five of these party columns, to wit: Republican, Democratic, Socialist, Socialist-Labor and Good Government.

The mayor and each city council members were each afforded half a column for any item they wished. The city appropriated $36,000 per year for the newspaper, or about a little over $1 million in today’s dollars. Advertising was accepted, but not for medicines or unlisted stocks, and ultimately made up a significant portion of the paper’s revenues.

The paper was overseen by three unpaid commissioners (an attorney, a physician, and Dunlop himself) appointed by the mayor and confirmed by City Council. Dunlop laid out his vision for the Municipal News in detail at a newspaper conference in Madison, Wisc., in 1912.

“Privately owned newspapers do not give the facts fairly, and the private citizen's right of free speech, the right to shout forth arguments upon the street corner or in a hired hall, does not put one in touch with any considerable portion of the population of a city of a quarter of a million or more,” Dunlop said.

Like a lot of idealistic anti-commercial journalism advocates over the ages (I count myself among them), Dunlop didn’t have a particularly high opinion of the masses’ reading preferences. Naturally, it has always been poor taste to blame the public itself for this. There must be some other answer.

"The present thirst for sensational, even depraved reading matter on the part of the reading public, is not wholly natural; its size and its intensity are abnormal,” Dunlop complained. “It has been nourished insidiously by evil newspapers themselves.”

Dunlop came up with a falsifiable theory: a good public option in the marketplace would drive the yellow press out of business. "Give us a high grade, publicly owned, daily newspaper, distributed free to every home in the city, and much that is bad in the other newspapers will cease to be profitable and will disappear."

You can guess where all this is going.

In March 1913, the Los Angeles Municipal News was voted out of existence 24,089 to 15,788 and died after 32 weeks of life. “The city auditor is conducting an investigation into the financial affairs of the Municipal News in order to explain the failure of the year's appropriation to cover more than eight months of expenses,” Alice M. Holden reported for The American Political Science Review.

It hadn’t helped that local Republicans had boycotted the paper and refused to submit columns, not wanting to mix government with party business. It also hadn’t helped that the city already had many other publications that reflected local factions’ particular political views.

The city’s progressive reformers “already had the ear of the L.A. Express and needed no other,” Stansbury wrote. “They drafted the charter amendment that voters endorsed in 1913, abolishing the new paper on the grounds that it would save the city money.” The local Chamber of Commerce also resolved to kill the paper, thinking it too friendly to the city’s government.

The vote’s low turnout, compared to the more popular initiative approving the paper’s creation, has been blamed on Angelenos’ exhaustion with the direct democracy that Dunlop loved so much. Voters had been “summoned to the polls five times for initiative, referendum, primary, general, and charter elections; to the degree they read newspapers they knew they faced three more elections by June 3,” Stansbury said. “Voters could be forgiven for staying home—and by droves and in all social classes they did.”

And so the Municipal News died, though it lives on today in the hearts of estimable public journalism advocates like Victor Pickard as an example of what’s possible. The Los Angeles Times wouldn’t fully professionalize (and move ideologically toward a more respectable center) for another 50 years, after more and more of the city’s newspapers died, unable to keep up with the Chandlers’ advertising juggernaut.

“A history of Los Angeles publications is largely a graveyard record,” Julia Norton McCorkle remarked in a poignant assessment for the Historical Society of Southern California a few years after the Municipal News' demise:

Probably there is no profession which suffers so much as journalism from brilliant and promising beginnings, steady downhill career, and hurried and ignominious endings. The spirit of risk, which is a necessary qualification for the newspaper man, seems to lead naturally to journalistic ventures. Los Angeles has her literary graveyard. That she also has a large number of living and flourishing publications is an indication of the size of her journalistic burying-ground.

Fascinating history. What do you make of journalism funded through grants and philanthropy ? I interned somewhere called the Bureau of Investigative Journalism in the UK on one of their local journalism stories. I’m curious about such funding for journalism, as I found that it *still* ultimately lends itself to bias around what stories are given attention and how, as the philanthropy is often issues-based. But perhaps this also depends on the donor.