The catastrophe of knowledge work waits to be beautiful again, and interesting, and modern

From "Mad Men" to the AI era, the problems of underconsumption.

Let’s say you’re a journalist, a writer, an academic, an analyst: a knowledge worker. Things don’t look so good for your professional class right now. Newsrooms won’t stop shrinking, it’s hard to sell manuscripts, DOGE cut your funding, the CEO thinks AI will replace your department. Do people know where information actually comes from, or do they think it just falls from the information tree? You wonder.

To the knowledge worker, it feels like the money is going to the wrong places. When there’s no funding for intellectual work, you stop producing knowledge. In economic terms, social welfare declines alongside output, which is another way of saying that it’s generally bad when smart people stop putting as much smart stuff into the world as they could. Or in even plainer English: Everything starts getting dumber. The sense of wasted intellect shrouds 2025 like a halo of wildfire smoke that won’t dissipate.

Except it’s even worse — and weirder — than all that.

When you zoom out and look at the master P&L spreadsheet that’s ruining your life, the numbers suggest the problem isn’t shortfalls of knowledge production. The problem is shortfalls of knowledge consumption.

To reframe the problem: Let’s say the knowledge worker is hell-bent on creation, regardless of what the traditional market might bear. You put the institutions in your rear-view, go outside the box, move into a garret, go indie, self-fund, get a grant. You can get the tools: It’s simpler and easier than ever to boot up a newsletter, podcast, launch a solo project or incorporate a consultancy and get the ideas out there. But who is this for, again? Self-promotion starts absorbing an alarming share of your mental workload. You can’t just be smart, you have to go out there and drum up business. “Cannot please, cannot charm or win / what a poet!” Frank O’Hara lamented in 1957.

The overproduction/underconsumption paradox is clearer to perceive in the mass markets of the entertainment world, though once you know what to look for, you start seeing it everywhere.

Hollywood promotional budgets commonly exceed the costs of film production because it’s often cheaper to make an expensive movie than to create the audiences to enjoy it. 16,385 video games were published on the Steam gaming platform in 2024, more than double the number released in 2019, even as the share of Americans who play video games slightly declined over the same period.

In the academic arena, the number of scholarly articles being written exploded 47% between 2016 and 2022, even as the number of people likeliest to read them, working scientists, remained stagnant.

These gluts might only feel like a new problem because the nature of information underconsumption was concealed to many producers for the past two decades.

The exploding size of the global market in the digital era connected billions of potential new consumers to what was originally a much smaller number of producers. Whether the competition was overinvested (intellectually or economically) in legacy business models or analog technologies, digital seers had some room to run, sometimes goaded ahead and floated by speculative bets from VCs on Sand Hill Road. Think of all the journalists now floating around Substack thanks to Series A investor Andreessen Horowitz.

But once markets stop expanding so quickly, competition increases, and market shares start eroding, things start to appear as they are and take on their proper shades of gray on gray. Creating stuff is hard, creating customers is harder.

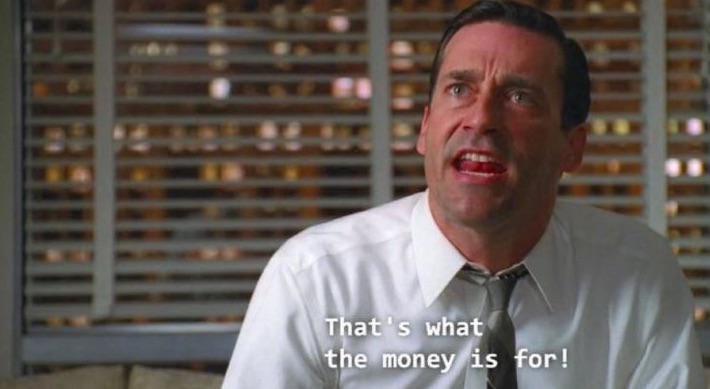

We’ve seen these hills before, just from a different time of day. The 20th century saw astounding advances in manufacturing power, which required a growing share of economic and intellectual energies diverted toward marketing. We’ve gotten really good at making Buicks — we just need somebody to buy them! Detroit begets Madison Avenue.

Perhaps Millennials remember growing up with a landmark television show about this great shift, and the well-compensated ennui involved in manufacturing demand:

But in the 21st century, when a postindustrial country like the United States is more competitive at producing IP instead of suitcases, economic resources are now shifting toward giving AI superhumanlike powers of information production and information consumption.

One obvious way to juice consumption is make robots do it. There are hard biological limits, after all, to humans’ attention spans and reading speeds.

We’re already automating demand. Crawlers are now the #1 consumers of journalism. The CEO didn’t have time to read your briefing paper — you should see her inbox — so she asks a GPT to scan it and recommend courses of action. (We’d probably be surprised how many CEOs have already offloaded not just reading but executive decisionmaking functions to AI.)

Neither can human marketers keep up with the machines in the business of generating consumption. Mark Zuckerberg’s Meta announced quarterly revenues of $46.56 billion, a 22% year-over-year increase, powered by successful deployments of AI that boosted the effectiveness of the company’s advertising platforms.

Meanwhile, traditional advertising houses are dying as the world’s Don Drapers draw fewer and fewer cultural insights through the delphic end of their cigarettes. Sydney Sweeney’s successfully trollish “good genes” ad campaign for American Eagle Outfitters was a gamble from advertising’s 20th century past, not its robot-driven future.

I don’t say all this to fearmonger for a robotic future and yearn for past consumer cultures. I’m just saying how weird things could be about to get. The situation isn’t just that AI might take our jobs. It’s that AI can take the place of customers, too. The AI might take on a role as tutor in many Americans’ lives, but in the background, some knowledge worker probably tutored the AI first.

It’s not a particularly idealistic situation. But it could be living.

You make me glad I'm old!

You might be surprised at the raw volume of job ads on LinkedIn for "AI tutors," a/k/a unemployed humanities graduates who have nothing to lose.