The journalist and the fury of the capitalist

On Adam Smith and the markets for writing.

Why do writers write? I write from a personal hatred of disorder. The world, at all times to me, feels in a state of unacceptable misalignment. Events appear inexplicably, unfold chaotically and unfairly, and are understood poorly by everyone.

So the journalist reads, watches, picks up the phone, sits at the keyboard to tidy up. What you see here is attempted decluttering. Though if you asked me why I published, we can’t ignore how our ungainly friend Vanity barged in and relocated the chairs to the center of the room.

But why do you read? My emotional state has nothing to do with why you’re still here in the third paragraph. (Analytics say most audiences don’t make it this far.) You’re busy. You could be doing anything else.

It is common among reformers and optimizers in the journalism world to exhort journalists to bridge this dangerous chasm between the interests of journalist and reader, to connect more directly and “meet people where they are.” Yet one of the great ironies of the digital era is that every material advance in digital distribution only pushes the journalist and consumer farther from an alignment of interests at every turn.

The search engine, recommendation algorithms, user-generated content, generative AI agents added layers of mediation, decreased frictions of dissemination, and by turns diminished the relevance of audience intent to the journalist while decreasing the intentions of the reader in seeking out this writer versus another. Information could, can and now does come from anywhere. The fact that many of my most diligent readers are probably AI crawlers only adds to the mystery.

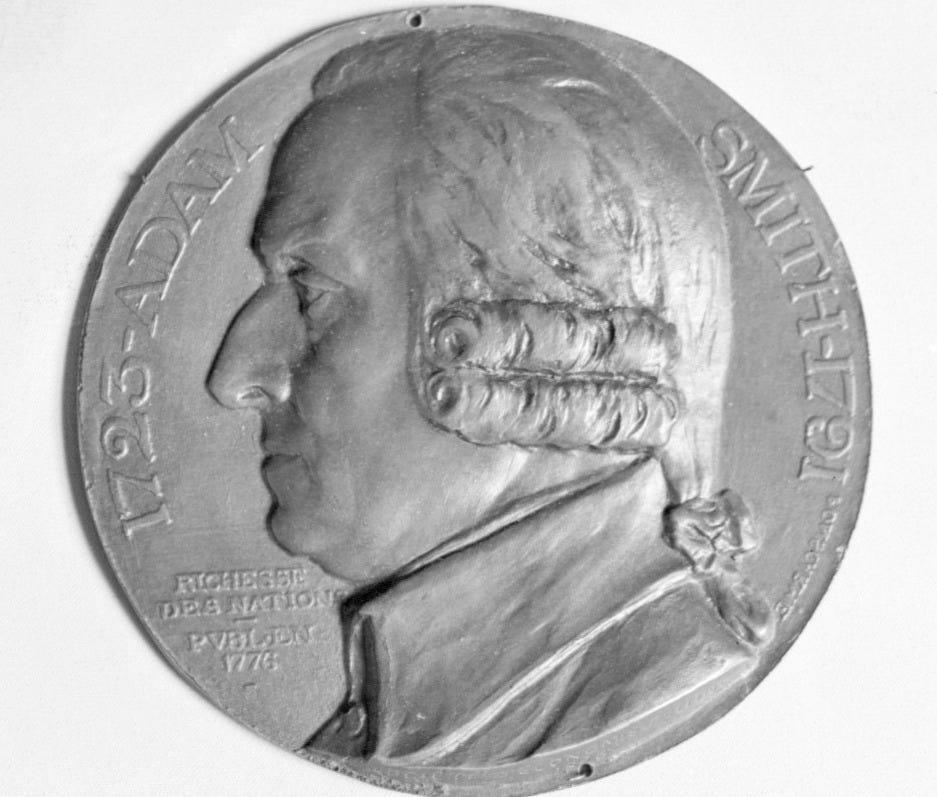

This growing estrangement from my own readers is the mere march of progress under classical economic doctrine, which for centuries has placed low value on needing to figure out why creators create and consumers consume: They just do, and generate the wealth of nations. The gigantic AI company operated by an insane tech impresario might be plundering the labors of a million writers and artists, but distributes the spoils to billions one slopping heap of bytes at a time. The human reader, missing me in one place, finds pieces of me in so many others. I don’t enjoy the idea of it, personally.

Writers, in many ways, have long known this kind of dislocation. I don’t, for example, need to read Adam Smith to have echoes of his free-market philosophy mirrored back to me through almost every institution and instinct of American life. But it’s more enlightening to visit the source material anyway, and to encounter something a little more unexpected: the raging passions of the Scottish author.

Smith’s infamous “invisible hand” of the markets metaphor, from his 1759 “Theory of Moral Sentiments,” appears in a virtuosic chapter where he acidly describes how much economic activity is powered by totally stupid, frivolous and misguided personal motivations. That chapter contains Smith’s story of “the poor man’s son, whom Heaven in its anger has visited with ambition, when he begins to look around him admires the condition of the rich.” A life of toil and envy awaits the striver, Smith writes; he “makes his court to all mankind, he serves those whom he hates, and is obsequious to those whom he despises.”

And then, when the poor man’s son has become old and wealthy and has won the game:

In his heart he curses ambition, and vainly regrets the ease and the indolence of youth, pleasures which are fled for ever, and which he has foolishly sacrificed for what, when he has got it, can afford him no real satisfaction. … Power and riches appear then to be what they are, enormous and operose machines contrived to produce a few trifling conveniencies to the body, consisting of springs the most nice and delicate, which must be kept in order with the most anxious attention, and which in spite of all our care are ready every moment to burst into pieces, and to crush in their ruins their unfortunate possessor.

If there is a case for reading, a case for human encounter in the written, it’s this: Waiting for you, as you turn the page, is the discovery that the godfather of capitalism was a moralist with a poison pen.

Matt...I wish you'd kept writing this and developed your ideas further. You have an intelligent lucid voice and your opening spoke directly to issues I grapple with personally. I feel you summed this up too soon.

Fascinating and brilliant! Thank you