The measure of a writer

Kaleb Horton and the remembering machine; Ezra Klein versus Ta-Nehisi Coates.

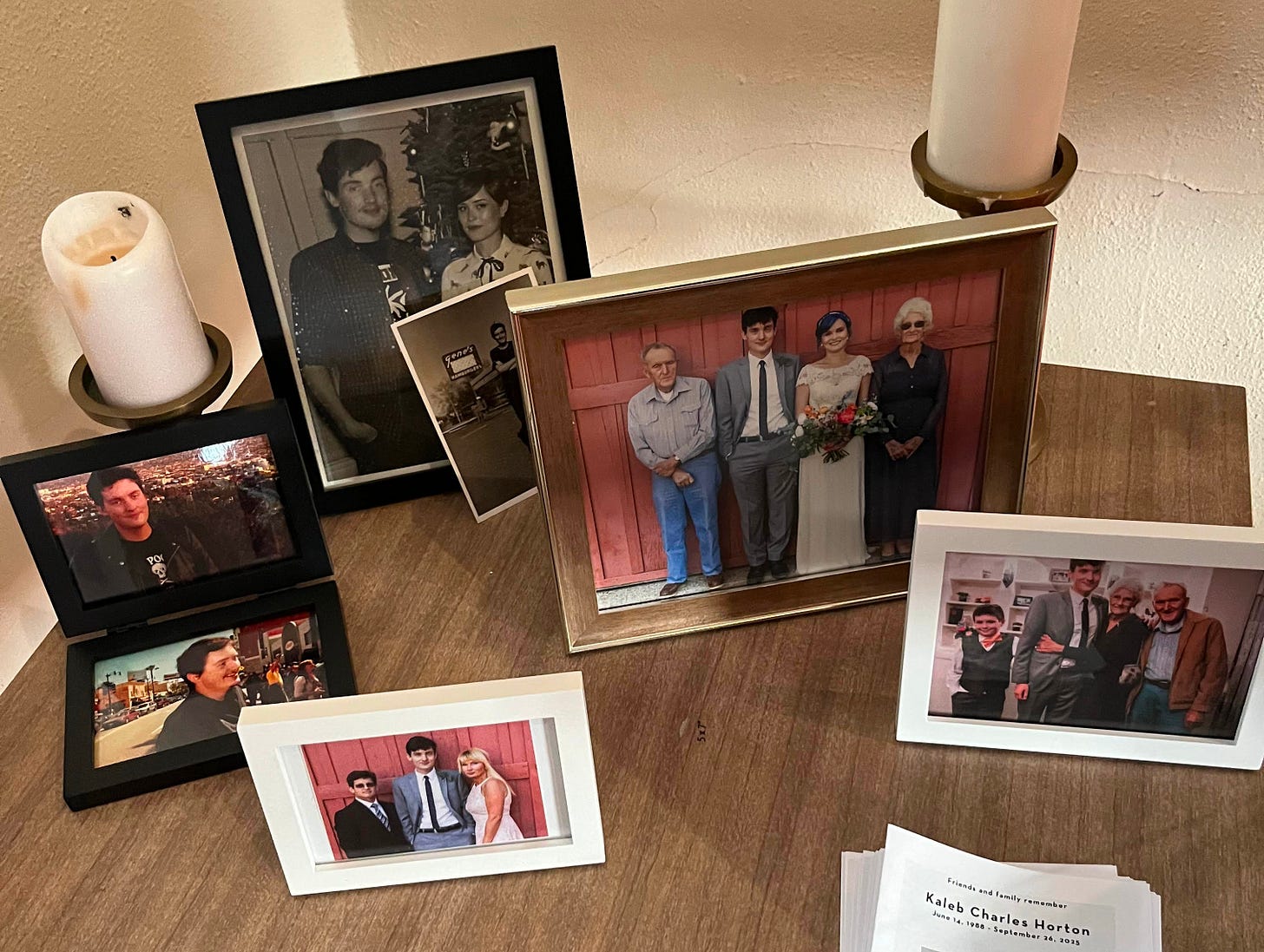

The great California writer Kaleb Horton’s memorial service was held at the Silver Lake Community Church in Los Angeles last week. It was a good event, with several moving tributes to Kaleb and readings of his work, including this by David Grossman. Since Kaleb’s death (said by his family to have been from complications related to a seizure), excellent remembrances have also been shared by friends and collaborators who knew him personally far better than I did, including Luke O’Neill, Ned Raggett, Stephen Thomas Erlewine, Holly Anderson, Conrad Flynn.

It bothers me there isn’t an independently reported obituary yet, some kind of arm’s-length acknowledgement of this life and its conclusion. The death was already deeply painful for those who knew Kaleb, his family, his loved ones; the survivors have assembled some small literary pyres to push back the void. But as a fellow writer, when I think about the idea of a talent passing unrecognized by our culture’s remembering machines, I see something that scares me. Here there once lived a man who awaits the stranger’s appraisal.

On another subject: I’ve been spent the last couple of weeks mulling over Ezra Klein’s interview of Ta-Nehisi Coates on Klein’s NYT podcast. It’s an educational episode featuring two ideals of the contemporary opinion journalist in conflict, with dueling progressive public intellectuals near the height of their influence under differing ethics. The site of the writers’ moral collision was the assassination of Charlie Kirk, whom Klein declared “was practicing politics in exactly the right way,” but whom Coates countered in Vanity Fair “subscribed to some of the most disreputable and harmful beliefs that this country has ever known.” Both writers claim to be confronting the world as it actually is; the existential difference comes in each’s understanding of their own journalism’s relationship with progress and progress’ relationship with historical time.

Klein’s rise into journalistic superstardom at the New York Times in recent years has aligned with a role as an intellectual organizer of the contemporary Democratic Party’s moderate wing. Klein was early calling for the Democrats to dump Joe Biden as the party’s nominee in 2024, which the party later carried out. Klein also coauthored the “Abundance” book that was the talk of many California Democrats in 2025, which (I’m simplifying somewhat) encourages progressives to explore a more deregulatory agenda to improve government effectiveness and voters’ standards of living. The event of a partisan’s ghastly killing accordingly yielded Klein’s call for conciliation.

Klein’s journalistic role is practical, as he described himself in the podcast:

I think that there is a work of politics that for a bunch of different reasons has become demeaned. … And I think that the idea that political coalition-building, building across these gigantic differences, building across public opinion — both not just as you wish it existed, but as it exists — has often become seen and treated as betrayal, cowardice, moral fallibility. I think it’s fine to say people have different roles, and, in fact, it’s good for intellectuals to criticize politicians. But my view is that the political practice became too weak. … One of the things I’ve thought about is the need to raise the status of old-fashioned politics.

“Old-fashioned” politics is the wrong phrase for it. What Klein is describing here is a majoritarian political ethic rather than a representational one: that is, a politics that wins to govern. This is the politics we already have! This isn’t the 19th century; we don’t have parties that represent the interests and day-to-day welfare of the working class or slave-owning white planters, win or lose. The modal American voter today is an independent, and swaying them each election requires increasingly expensive media and organizing outreach campaigns. The voter’s choice of party (if any) — like their choice of media — is an effectively random decision at the individual level. Accordingly, our modern parties are abstract, complex statistical entities optimized to win elections from whatever coalitions of partisans and independents that can be cobbled together. The majoritarian’s mandate is to win rather than to represent. That’s why the majoritarian’s organizing logic sometimes requires dumping or marginalizing voices whose presence has become inconvenient. Voices like Ta-Nehisi Coates.

Coates comes from America’s rich, longstanding tradition of Black intellectual and journalistic inquiry, which for obvious reasons has often flourished outside of majoritarian modes of thought. Coates burst into public renown a decade ago at “The Atlantic,” grandly with his “Case for Reparations,” but more epically with his post-Ferguson book “Between The World and Me,” after which Coates retreated from journalism somewhat into creative lines like writing for comic book series. Coates re-emerged a last year with a visit to the West Bank and concluded, at almost the precise moment when it was riskiest for his mainstream career to do so, that the Israeli occupation was tantamount to Jim Crow. Recently, Coates swam into the hysteric McCarthyist aftermath of Kirk’s assassination to write the kind of things that were getting other unfamous Americans fired from their jobs.

Coates’ journalistic role, unlike Klein’s, self-consciously follows the old-fashioned representational mode of politics rather than its more modern and abstract majoritarian cousin. In the representational mode, sometimes the people you represent are defeated in this lifetime, but you don’t give them up. On Klein’s podcast:

I’m Ta-Nehisi Coates, I’m the writer, I’m the individual, right? But I am part of something larger, and I’ve always felt myself as part of something larger. I have a tradition, I have ancestry, I have heritage. What that means is that I do whatever I do within the time that I have in my life, whatever time I’m gifted with, and much of what I do is built on what other people did before them.

Then, after that, I leave the struggle where I leave it, and hopefully, it’s in a better place. Oftentimes it’s not. That’s the history in fact. And then my progeny, they pick it up, and they keep it going.

I am descended from people who, in their lifetime, fought with all their might for the destruction of chattel slavery in this country. And they never saw it. They never saw it. In my personal belief system, they died in defeat, in darkness.

So I guess the privilege that I draw out of this, the honor that I draw out of this, is not that things will necessarily be better in my lifetime, but that I will make the contribution that I am supposed to make.

If you’re this kind of seer, then you always know where you’re standing and who you’re standing next to, even when it’s in the nighttime of civilization and pitch black outside. (Coates: “I’m all for unifying, I’m all for bridging gaps, but not at the expense of my neighbor’s humanity. I just can’t.”) But when you’re in the majoritarian mode, you’re… whatever you need to be. Well, what is that? “Would you define for me how you see what your role is?” Coates asked Klein, perhaps the biggest star at America’s largest and most august journalistic institution. “I don’t know what my role is anymore,” Klein responded. “I’ll be totally honest with you, man. I feel very conflicted about that question.” This uncertainty may be an existential dilemma at the level of personal conscience, but it’s not a huge problem in the journalistic or political arenas. The path to a majority is paved with exactly these sorts of ambiguities.

So, give or take, journalism and politics for Klein is... a career. There are already words for everything. Diplomacy, for instance, is an age-old word that includes bridging gaps, building coalitions etc. etc. But what for? To stop wars. That's it. To stop killings. To stop violence. To establish peace without anyone conquering or surrendering. Not to water down your political convictions until they look like your opponent's. There are other words for that. Career is the most kind, probably. BTW, there's a colloquial phrase in Greek that means "who cares"... It's "Klein mein"!

Dear Matt, Thank you for this. Very insightful and thought-provoking for me, a different point of view than I take. Klein’s answer to the question of how he sees his role was very revealing. He sees himself as …… successful, and what else?