The Millennial reader to medieval priest pipeline

When reading wins, what does the reader lose?

Now that I no longer have a job where I have to make money solely from writing words, I feel less gloomy about the state of reading. This was admittedly not an honorable or even rational change in attitude. “If you read a book in 2025—just one book—you belong to an endangered species,” The Atlantic warned last month, citing the scary trends of declining reading habits and skills. Kids these days… My own path toward a literary lightness of being was partly biochemical. All the bad stimuli that came with being a maker (why am I not getting paid more, how many of my coworkers are getting laid off now?, gosh the latest audience analytics say something dark about human nature) got replaced with the happy stimuli of being a pure consumer. To make is to suffer, but consuming stuff is fun. So many options! Thank you for this nice red button, yes I’ll have more pellets please.

But something bothered me during my conversion from aggravated producer to luxuriating consumer. I didn’t feel in control of my own attention.

More precisely, I wasn’t happy with where my attention always wandered: away, toward junk. TikTok was really fun, but I hated being channeled via design choice away from focusing on anything for longer than 30 seconds. I loathed how Meta algorithms spied on and overreacted to my smallest lingerings on a given subject or product. The monofeed of Bluesky (X is dead to me) efficiently updates me on human rights abuses by the second Trump administration, but saving democracy is heavy on hard news and light on the liberal arts that make the democratic life worth living. And the idea of chatting with an AI summoned no pleasure whatsoever, just the astronaut’s horror of staring into a starry but ultimately lifeless void. Every LLM user is alone in the universe.

To truly enjoy myself as a layabout consumer, I realized that I had to become a better, more disciplined, more devout reader.

This would require work. Attention is a zero-sum game, at least as an accounting matter. Paying attention to one thing fully is to ignore everything else. To pay better attention meant sacrifices were needed. Like a private equity executive sweeping away old lines of business to refocus on core operations, I brutally reallocated my attentional capital. I deleted TikTok entirely and imposed a daily time limit on my iPhone of one hour for social media apps, plus 30 minutes for Substack. I finally faced facts about an increasingly unmanageable email intake and accepted the reality of inbox insolvency: the options for response are 1. now or 2. never. I set a goal of reading roughly a book a week in print.

The impacts in the quarterly attentional report are substantial so far, a real earnings beat. I’m spending less time on microposts in feeds and more on fulltext stories in news apps. My 2026 book completion pile is growing ahead of schedule with a satisfying mix of fiction and nonfiction. A short-form video hates to see me coming (though I liked this well done NYT feature on the death of mass market paperbacks).

Now I’m smugger and more out of touch than ever. It feels great. And I’m not alone. Last year, The Cut asked other super-readers how they find the time, which yielded this lovely account from famous person Nicole Richie:

I read whenever I can. While I don’t have a lot of rules around my reading, I do have a few little habits that keep my reading flow in forward motion. Whatever book I am reading is next to my bed, because I love to read in the morning. I wake up around 5:30 a.m. when everyone else is asleep and that is my reading time. I have not yet checked my phone or any electronics so my mind feels focused and ready to lock into a story. It’s usually a novel. I love reading fiction at home in bed.

I also always carry a book on me. I have a few smaller books of essays I keep in my car, and whatever novel I am reading goes with me everywhere. I like a good old-fashioned book. I feel connected to my book by holding it, flipping through it, bending it. When it’s on me, I can read a page or two whenever I can. I never read without a pencil. I underline and write notes in the margin while I read. I don’t really lend my books to friends because most of the books I have too many personal notes in them.

To declare a victory of reading for the reader is not to declare a supremacy of writing in the culture. But a reading discipline reopens doors that would otherwise be bricked off, like reacquainting myself with Italo Calvino’s generous mind via his essays collected in the Mariner Classics’ “The Written World and the Unwritten World.”

Shortly before his death in 1985, and shortly after the Argentinians had restored their democracy in 1983, Calvino attended the Feria del Libro bookfest in Buenos Aires and swooned at being “in a climate of freedom regained,” surrounded by the new:

Speaking to you here at the Feria, I want to try to analyze the sensation I have whenever I visit a great book fair: a kind of vertigo as I get lost in this sea of printed paper, this boundless firmament of colored covers, this dust cloud of typographical characters; the opening up of spaces like an endless succession of mirrors that multiply the world; the expectation of a surprise encounter with a new title that piques my curiosity; the sudden desire to see reprinted an old book that can’t be found; the dismay and at the same time the relief in thinking that my life has scarcely enough years to read or reread a limited number of the volumes spread out before me.

These sensations are different, by the way, from those which a great library offers: in libraries the past is deposited as if in geologic layers of silent words; at a book fair it’s the new growth of the written vegetation as it propagates, it’s the flow of freshly printed sentences trying to channel itself toward future readers, pressing to spill into their mental circuits.

Still, even at a time of democratic renewal, readers fretted to Calvino about a decay of the literary. “You speak of books as of something that there has always been and always will be, but are we really sure that the book has a future ahead of it?” Calvino says readers customarily ask him at a festival. “That it will survive the competition of audiovisual electronic devices?” To this, Calvino commands: “Loyalty to the book, come what may.”

The important thing is for the ideal thread that runs through centuries of writing not to break. The thought that even during the Middle Ages of iron and fire, books found in convents as space where they could be preserved and multiply on the one hand reassures me, on the other hand worries me. The idea that we should all retreat to convents endowed with every comfort to publish books of quality, abandoning the cities to the barbarian invasion of videotapes, might even make me smile; but I wouldn’t like the rest of the world to be deprived of books, of their silence full of whispers, of their reassuring calm or their subtle disquiet.

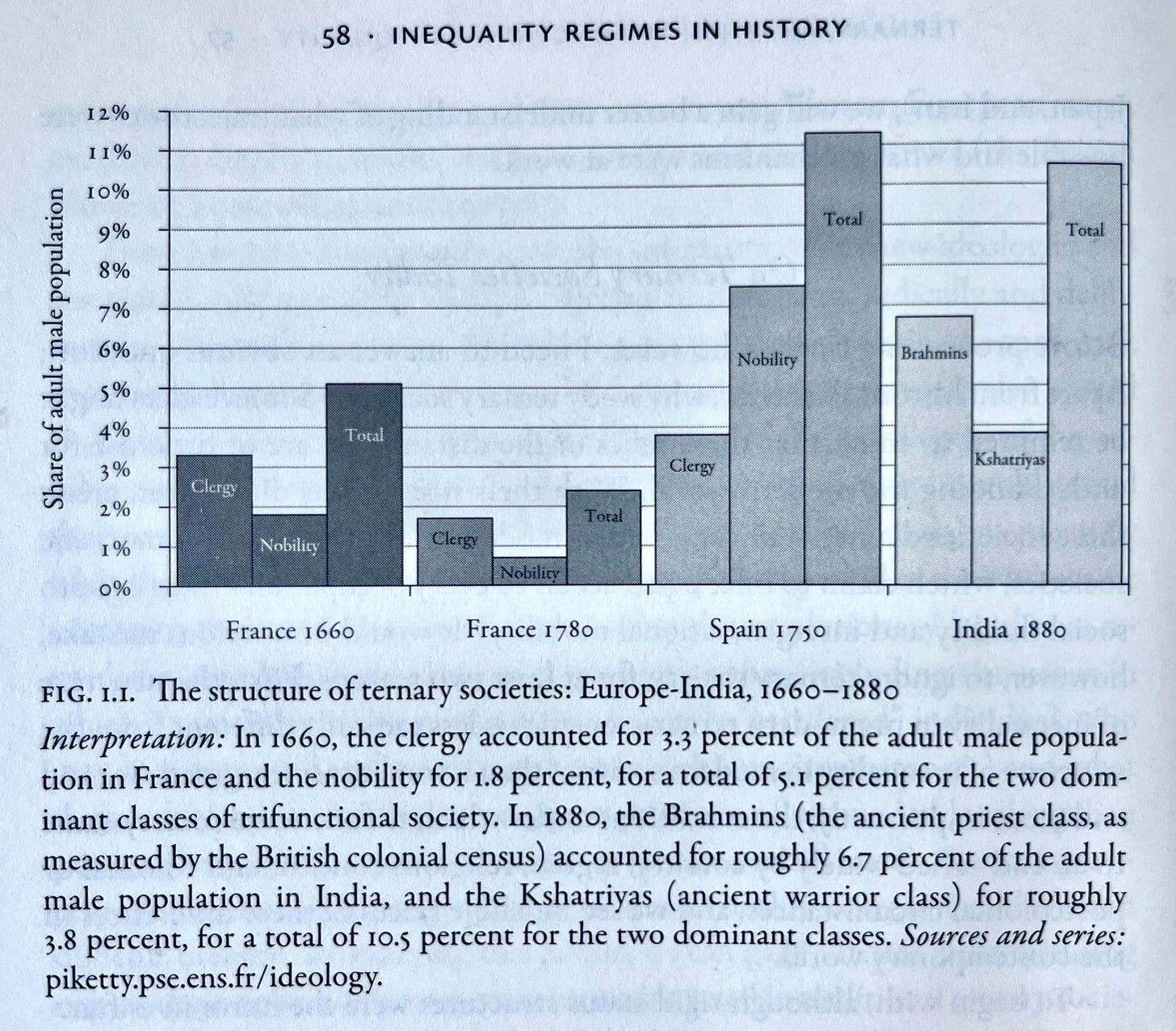

From the perspective of 2026, conditions for the avid reader are certainly more monasterylike than in Calvino’s time. Four percent of Americans told YouGov in December that they were reading about a book a week, which, according to the Thomas Piketty I’m currently reading, is roughly equivalent to the size of the clerical class — the meaning-makers — in predemocratic societies:

Am I making myself some sort of medieval priest, holed up in a monastery overlooking a postliterary landscape? Maybe? Reading so much won’t make you feel like a revolutionary leader as much as a caretaker, a keeper of small flames. It’s mass culture that renews mass culture, if that’s what you’re looking for. “There has always been a culture industry, containing the danger of a general decline of intelligence, but something new and positive always emerges from it,” Calvino wrote of the rise of television, for instance. “I would say there is no better terrain for the birth of true values than that which has the stink of practical requirements, market demands, consumer production: that’s where Shakespeare’s tragedies originate, Dostoyevsky’s serial novels, and Chaplin’s comedies.”

Still, even as a young man growing up amid a mass literary culture, Calvino aspired to be a “minor writer,” because “those who were called ‘minor’ were the ones I liked best and felt closest to.” Even lonesome clergies tend to be fraternal.

Brilliant take on the zero-sum nature of atention. What really got me thinking was the private equity metaphor for attention reallocation, since I've actually had to do similar portfolio analysis in my work and never considered applying it to my own mental bandwidth. The monastry comparison is apt, but maybe there's a third path where deliberate reading becomes social rather than isolationist (book clubs making a comeback?).