Understanding Lina Khan and the Millennial class war

Millennials' generational struggle against Boomers is ending where it always would: old-fashioned class war.

I was talking to an older acquaintance recently, a Gen Xer corporate executive, who was vexed by Mark Zuckerberg’s style transformation: the curly hair, the necklaces, the casual shirts. “He looks so stupid,” she said. To which I replied, absolutely: He is dogwhistling to Millennials now, and specifically to Millennial men. Like me, I guess.

What’s important to understand is that Zuckerberg, 40, believes he is engaged in a generational war with Boomers, and the Facebook founder has been making plans to win that war. If not on behalf of his fellow Millennials, then at least on behalf of himself and his company.

“Many important institutions in our society (eg education, healthcare, housing, efforts to combat climate change) are still run primarily by boomers in ways that transfer a lot of value from younger generations to boomers themselves,” Zuckerberg wrote in a private January 4, 2020 email to fellow tech machers Peter Thiel, Marc Andreessen, Sheryl Sandberg and Nick Clegg, which was obtained by the Tennessee Attorney General’s office in a lawsuit filed against Meta. “Our macro prediction for the next decade is that we expect this dynamic to shift very rapidly as more millennials + gen Zers can now vote and as the boomer generation starts to shrink.”

Thiel had nudged Zuckberg to move away from “a Baby Boomer construct of how a well-behaved Millennial is supposed to act,” he wrote. (Think of Zuckerberg in a suit, tie, and close-cropped hair testifying wanly in front of a gerontocratic Congress.) “If forced to make a choice, I would always rather win popularity contests with Millennials than with Boomers!”

Time to pivot. “We want to be on the side of the future,” Zuckerberg wrote. The future looks Millennial, and as far as Millennials go, “I am the most well-known person of my generation.”

You could argue the case for Millennial megastars Taylor Swift, 34, LeBron James, 39, or Lionel Messi, 37. (Beyoncé, 43, is an Xennial cusper.) But what sets Zuckerberg’s peers apart is that they are the world’s most famous workers. They are each certainly business enterprises unto themselves. But Taylor Swift only reached god-empress cultural status in recent years by grinding out albums and spending three and a half hours every night on that stage. LeBron and Messi have spent their entire careers with bosses. At the heart of it, each of these people have to take showers after work.

Zuckerberg’s path was to work smarter, not harder. His fundamental insight into the value of social networking was to make other people do the work for you. He started with ripping off classmates’ photos from the Harvard dorms to pit people against each other based on hotness. (Harvard accused Zuckerberg of violating copyright.) It turned out the more durable model was persuading people to upload photos all on their own; Mark just owns the space where people store their stuff online. I don’t know if Zuckerberg is our most famous Millennial, but he is our most famous landlord.

For Millennials, most of whom are workers, almost our entire life has been marked by these kinds of subtle but massive wealth transfers from workers and consumers to corporations and their investors. At the same time the Great Recession shattered the job market in 2008, employers had already been shifting more risk onto workers, either in the form of more intense education requirements (funded by student debt and rising tuition rates) or in fissured gig work with lower pay and fewer benefits.

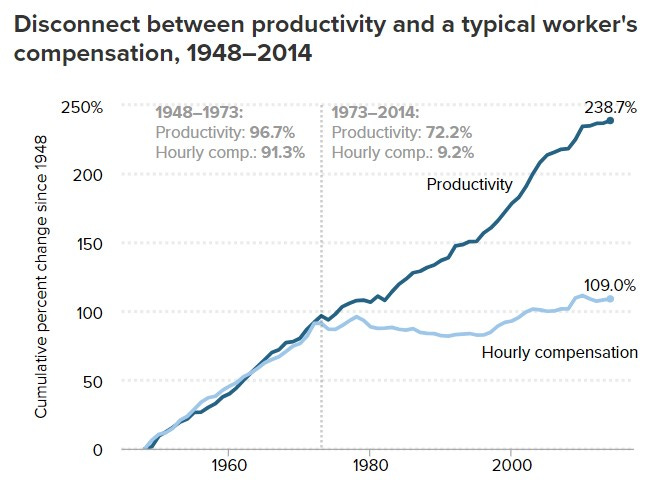

Millennial workers, in short, were entering an economic world marked by a major decline in worker power, in which productivity and profits had increased while wages didn’t keep pace:

Zuckerberg knows all this! He’s emailing Peter Thiel about Boomers hoovering up wealth from Millennials! He’s talking about remediation! “Perhaps there are specific things we could do to make housing more affordable with an emphasis on younger people who don't have large families yet,” Zuckerberg wrote. “Or given that so many people graduate college today burdened with crazy amounts of debt, perhaps we should have a larger program for hiring people who didn't go to college to help show that that's a reasonable path as well.”

Zuckerberg’s presumption seems to be that if you just get some Millennials in power, things will run a little differently. More distributively, perhaps. And maybe that’s true. Just look at who’s become one of his greatest nemeses: “hipster antitrust” champion Lina M. Khan, 35 the youngest-ever chair of the U.S. Federal Trade Commission.

If there’s anything to make of Khan’s electrifying revival of the FTC from a sleepy federal bureaucracy into a vital force for accountability, it’s that the Millennial generational war will just roll over into some good-old-fashioned class war — rebalancing the scales between takers and makers, between scammers and the scammed. All you need to do is watch these 90 seconds of Khan talking about why asthma inhalers that cost $7 in France cost $500 in the United States to get why a lot of younger people have been rooting for her:

If you are somehow reading me nattering on here about labor markets and tech monopoly power and how it affects journalism but somehow don’t know what Khan’s deal is, I’d point you toward this excellent new profile in Bloomberg Businessweek by Josh Eidelson and Max Chafkin:

Khan is among a handful of Biden appointees who’ve taken a firm hand with business. US Department of Justice antitrust chief Jonathan Kanter won a federal trial ruling Google a monopoly and is suing Apple Inc. SEC Chair Gary Gensler has been pushing back on the crypto industry. It’s Khan, though, who’s been the tallest lightning rod for America’s loudest rich dudes. Demographics may have something to do with it. It’s Khan who’s the woman of color, who’s Muslim, who’s 35 years old, who finished law school when Trump was president. As new as she is to Washington, she’s not focused on ingratiating herself with the old boys’ club. “A lot of people in the back of their heads are thinking, ‘Yes, I’m going to be tough. Yes, I’m going to be aggressive. But I do care if, when I’m out of this job, Fortune 100 companies are going to hire me,’ ” says fellow FTC Commissioner Alvaro Bedoya. “I don’t think Lina cares what they think about her in Davos or Aspen. That thought does not cross her mind.”

If you didn’t feel a bit of a thrill in reading that last quote, this newsletter may not be for you. A lot of the most powerful people in the country really hate Lina Khan, on a bipartisan basis! Just look at these three incredible paragraphs:

Khan’s agency derailed Nvidia Corp.’s acquisition of chip designer Arm Ltd.—and tried to stop Microsoft from buying the video game giant Activision Blizzard and Meta from buying the virtual-reality app Within. Although judges ruled against Khan on the latter two (the FTC is appealing the Microsoft decision), venture capitalists argue these fights create a climate of fear, hurting small startups by making it harder for them to sell themselves off to big ones. “SHE’S KILLING M&A & BREAKING THE VENTURE INDUSTRY,” tech investor Jason Calacanis posted on X in August. He attached a chart showing declining VC returns and called Khan a “COMMUNIST,” adding “THESE LUNATICS HAVE NEVER BUILT ANYTHING OF VALUE.”

Calacanis’ all-caps sense of betrayal is becoming more common. What bugs many of Khan’s critics isn’t simply her approach to policy, but the way she talks about them. “The underlying tone is like Elizabeth Warren,” says Mark Pincus, who founded video game company Zynga and now works as an investor. Pincus tried to persuade Warren to back off her criticism of tech giants. “When you attack Amazon, you’re attacking America,” he says, recalling one of those conversations. “It’s providing all the jobs and paying all the bills.”

There are costs, some of these critics warn, to picking on allies. “She’s hitting the pocketbooks of Biden donors,” says Dmitri Mehlhorn, who co-founded an advocacy group with Hoffman and was his political adviser until earlier this year. “The money that was going to be given to Democrats isn’t there.”

Whenever you encounter somebody saying something like “when you attack Amazon, you’re attacking America,” you have grabbed onto one of the broken power lines of U.S. politics that just might kill you unless you’re wearing rubber gloves.

Democratic presidential nominee and Vice President Kamala Harris hasn’t signaled whether she’ll keep Khan, who is apparently thronged by young people when she visits law schools and town halls. Some of Harris’ powerful supporters have been rooting for an ouster, most recently Mark Cuban — a Gen Xer, like many of Khan’s critics.

It’s prompted a rally-around-the-flag effect for many of Khan’s supporters. “Let me make this clear, since billionaires have been trying to play footsie with the ticket: Anyone goes near Lina Khan and there will be an out and out brawl,” Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, 34, tweeted yesterday. “And that is a promise.” Another past supporter? Republican Vice Presidential candidate and Senator J.D. Vance, 40, who said in February, “I look at Lina Khan as one of the few people in the Biden administration that I think is doing a pretty good job.”

Historically, matters of corporate regulation have been marked by clear partisanship, and that’s probably still true in the near-to-middle term. But the scuffle around Khan’s legitimacy and her future has taken on a growing generational cast, with Millennials of different stripes, and the Zoomers emerging behind us, acting somewhat more skeptically of private power than our predecessors. Only a minority of us will get to be the Zuckerbergs who benefit most from a scammer economy; maybe that’s why so many of us see ourselves in the Khans fighting hardest for change.