The economist Albert O. Hirschman studied when people quit in his famous book “Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States.” When situations go bad, you can try improving things by complaining, or leave for greener pastures. Agitation or exile. Many reasonable people from all eras and corners of the world, including many brilliant and influential ones, have left their jobs, their homes, pulled up stakes and crossed rivers, fields and mountains, sometimes across borders, even into statelessness, because it was the better choice. To every thing there is a season, and exit is a winter. It’s ice cold, but sometimes you just have to throw a jacket on and get the fuck out of there.

Hirschman’s curiosity with quitting didn’t come casually. He was a Berlin-born Jew who fled multiple nations (and joined three armies) because of fascism, famously helping smuggle Hannah Arendt and other thinkers out of Vichy France as the Nazis closed in. Exit is one of the recurring historical experiences of the intellectual, with the usual culprits of religious intolerance, absolutism, violence. “Passions bring men closer together while the need to stay alive obliges them to flee from each other,” as Hirschman quoted Rousseau, another historical exile from France, years later.

But what about staying? This week, Atlantic alum Jerusalem Demsas launched a new digital publication called The Argument, which aims to make “a positive, combative case for liberalism through rigorous, persuasive journalism.” I commend Jerusalem and her fellow writers on their ambition, given how hard it is to accomplish anything sustainable in media right now. I wish them well. And offer a humble in-kind attentional donation by taking up Jerusalem’s obvious troll-bait, titled “The case for staying on Twitter.”

Or as the story slug on the URL puts the issue more directly, “we-have-to-stay-at-the-nazi-bar.”

No you don’t.

There are powerful historical precedents and arguments for the upsides of quitting the proverbial “Nazi bar.” The personal biographies of great writers like Hirschman, Arendt, Thomas Mann, Leo Strauss, and so on and so on, demonstrate the vitality of influence possible even in exile. Many of our best and brightest were famous Nazi bar quitters.

These thinkers’ motives were less about utilitarian hopes of maximizing persuasion, making change than the untenability of a status quo. The circumstances of Hitlerism were unique and extreme. But the general principles involved in flight are timeless, as Hirschman knew.

In the much lower-stakes context of Twitter, I’m a power-quitter — walked away from something like 150,000 followers and years of relationships on the service. I’m not a purist who exercises a politics of sanitation and separation as a demonstration of my moral righteousness; I’m public-facing, and utility is a basic necessity for me. (You may have noticed I’m still on Substack, which has its own Nazi bar problem.) I support a culture of encounter in journalism, politics, and thought. A principle of my trade unionism is to create conditions for collective improvement rather than just dumping problems on the next poor bastard — improving flawed environments through what Hirschman calls “voice.”

But I left Musk’s Twitter (which was already problematic and deteriorating before Elon’s acquisition) because prospects kept deteriorating for the things I really cared about. The product was bad! The platform depressed outbound hyperlinks to my writing, prioritized and incentivized slop on the feed I was seeing, and many of my favorite posters had long wandered away. This is on top of the baseline cognitive tax of spending too much time on the infinite scroll.

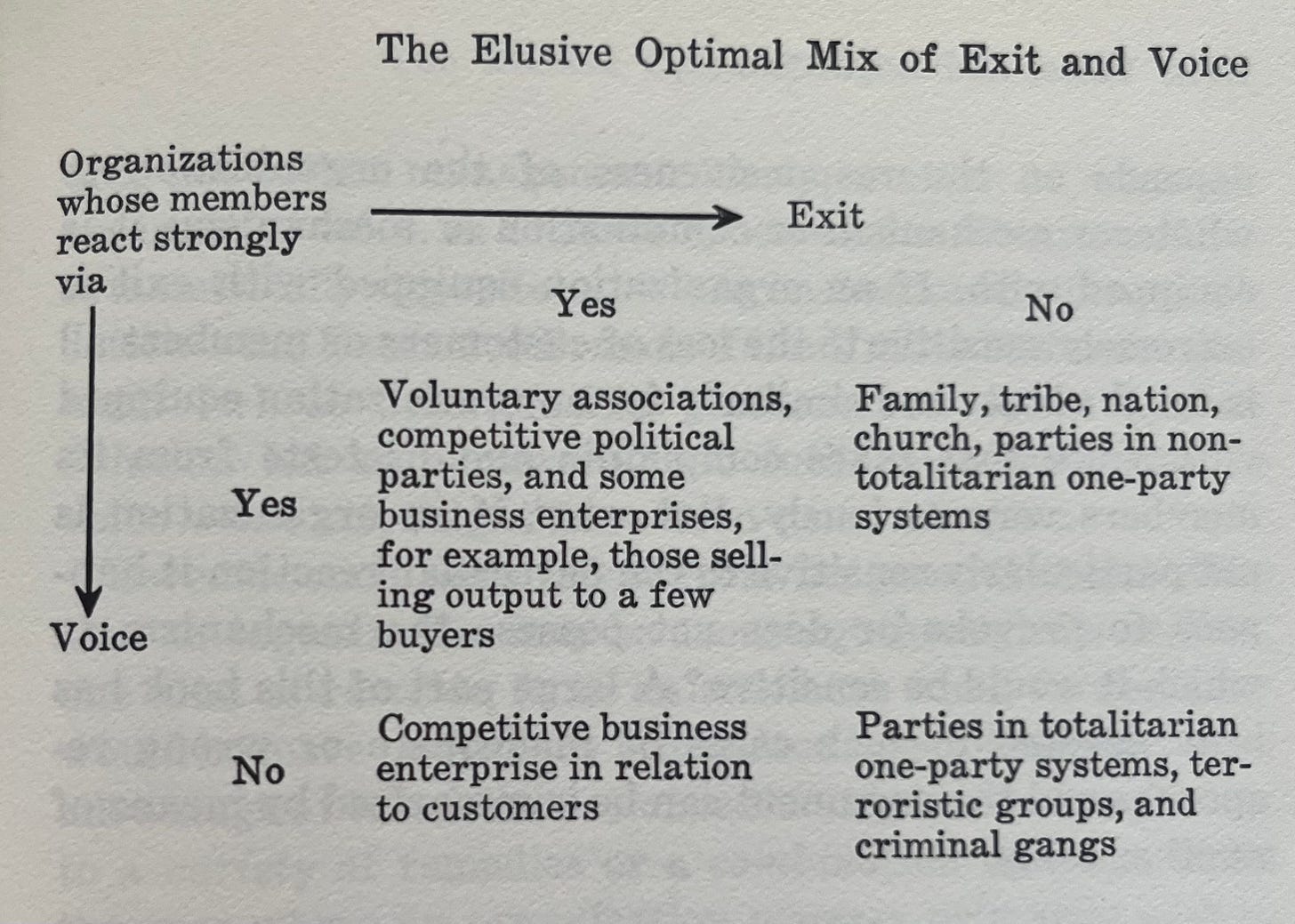

Nor were there prospects for improvement. The proprietor didn’t seem to give a shit about the deteriorating output and whoever was leaving. Certain entities in life don’t care if you complain OR if you quit, Hirschman noted, and they aren’t the kind to reform themselves:

Some of the people who abandoned Twitter before I did may well have been moral purists. I have a more empirically supportable suggestion: They were driven out. Workplace research already amply shows how harassment cesspools are bad for participation and productivity. The same dynamic goes for social platforms. Negative user feedback drives down how many YouTube videos women creators make, and accordingly what users see, relative to men. It’s not a public square if it’s missing too much of the public, not that Twitter was all that representative to begin with.

I won’t argue against anthropological and journalistic cases for observing a rotting cultural milieu, especially if that’s where newsmakers are. That’s the job. And in either case, well, look around. It’s not a huge stretch to notice that our new media regime of charismatic, afactual, personality-driven short-form content seems perfectly compatible with a politics of Putinist social cynicism and humiliation. Just don’t conform to it, and certainly don’t make a case for it. The biggest danger of any madding crowd, apart from being trampled underfoot, is joining in.

I doubt many of my old followers on Twitter actually miss me. The internet has a goldfish’s memory. If you’re not posting, you’re history, and most people don’t care about history. I run into old mutuals every now and then, and often they’re not sure what I’m up to these days. That’s exile.

But more and more, I bump into the occasional someone who (I am surprised to learn) reads this casual newsletter, and the acknowledgment feels far more flattering. This thing is far more work than the tweets were, both for me and for you, especially whenever I’m ranting about Hegel again. I have more mental space and energy to read challenging books and let my mind wander off-trail. I’m currently picking through Piketty’s massive “Capital in the Twenty-First Century,” which I didn’t even attempt summiting when it first came out, when I was busy posting and scrolling a lot more. I’m not trying to build followers, really, but it nonetheless feels like I’m building a new foundation.

Not everyone exits, of course. There are vain cases for sticking with what you know, like Twitter, but also masochistic ones. “She'd have thrown herself into the water long ago if it were not for me,” Rogozhin says in Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot. “She doesn't do it because I am, perhaps, even more dreadful to her than the water.” Toxic relationships have their romance, but it’s the doomed kind.

I can’t remember where I first read you, surely it was the LAT? So I followed you on Twitter and when you left Twitter I happily followed you here. I really enjoy the extra work we both do here in this communication. Thank you for that, I appreciate what you have to say in such a thoughtful way.

Well said. I also left Twitter years ago with much the same level of following (around 140,000 I think) and never looked back. Once in a while I hear someone say, "The people there don't miss you as much as you think"—which I always find a little weird, because I don't think they miss me at all!

As you said, most people aren't sitting around waiting for your next post. My decision to leave was about me and what I believed to be morally correct. Most of the time I honestly feel better not being there, so I don't have much FOMO about it.