Big Tech is behind those creepy "oppose AB 886" ads in California

The latest attack on the California Journalism Preservation Act is showing up on TV and social media.

Last week, I had the odd pleasure of encountering new ads from the Computer and Communications Industry Association opposing one of the major pieces of journalism jobs legislation my Guild supports, Assembly Bill 886, also known as the California Journalism Preservation Act.

It’s not the content of the CCIA ads that I like, of course; CCIA is a global Big Tech lobbying front headquartered in Washington, D.C., whose members include trillion-dollar multinational companies like Meta, Google and Amazon. These are not people anybody should get their local journalism policy advice from.

But as I noted on social media the other day, if these people are running opposition ads on TV and Instagram, it’s because the legislature is at risk of passing a law that might actually do something.

Here’s the full narration from the CCIA ad:

Our local news keeps us informed when others won’t. But it’s under siege from big, out-of-state media companies and hedge funds. Now California legislators are considering a bill that could make things even worse by subsidizing national and global media corporations while reducing web traffic local papers rely on. So tell lawmakers: Support local journalism, not well-connected media companies. Oppose AB 886. Paid for by CCIA.

I’ve heard from a couple of people confused about these tricky ads — wait, am I supposed to support journalism by opposing the journalism bill?

So for those of you encountering these ads, this legislation, or even the problems facing the local news business for the first time, here’s a basic primer.

The economic crisis in local news

In recent decades, the bottom has fallen out of the economic foundations that once supported the lion’s share of local news production. More recently, Google and Meta (and increasingly Amazon) have used their scale and acquiring power to become the central brokers of surveillance-driven digital advertising on the internet. News companies used to be the entities who provided advertisers access to the public. Now it’s the other way around.

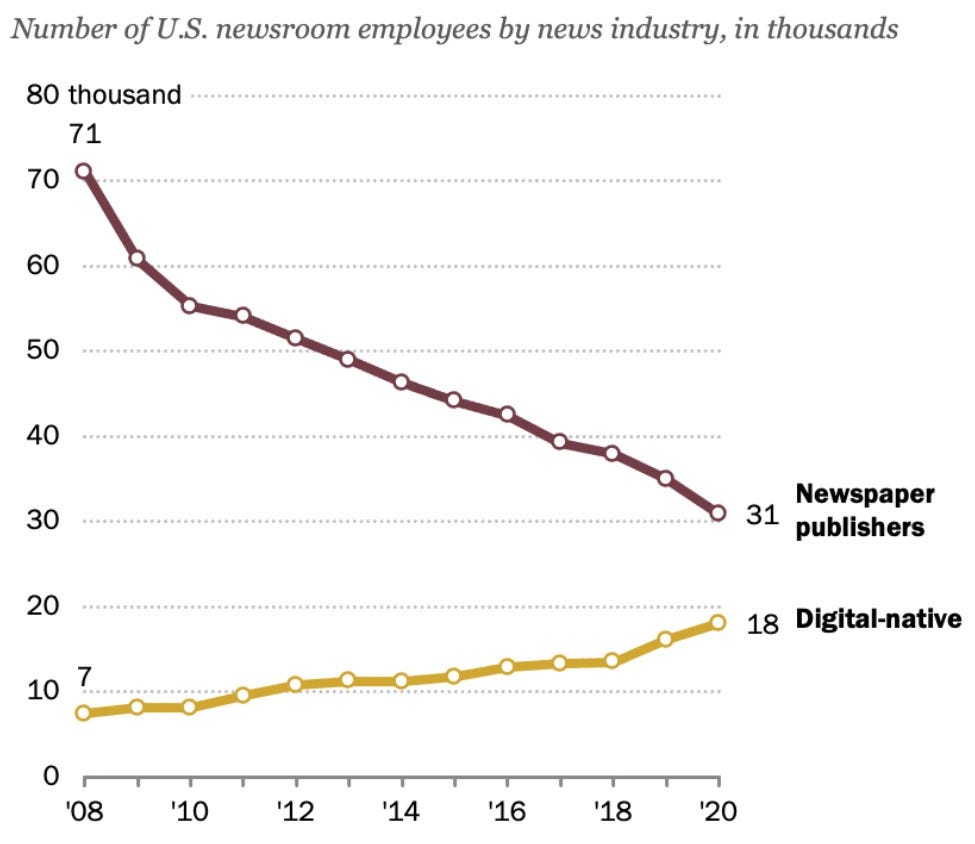

The results of this hyper-concentration of corporate power in digital advertising and distribution — and the decoupling of advertising revenues from the costs of journalistic production — have been devastating. Since 2000, newspaper industry employment has fallen more than 60%, a steeper drop than coal mining. Nor has this been creative destruction. Our 21st century digital-native and nonprofit local newsrooms have not come remotely close to replacing the journalistic capacity of their 20th century predecessors:

The view from California’s local newsrooms

Although we love yelling at private equity around these parts for decimating many U.S. local newsrooms, in recent years what’s happening to local journalism in California has become much uglier, exactly because most of our recent newsroom crises lack a nexus to Wall Street. What’s the name of the hedge fund that’s been gutting public-media broadcasters KCRW, LAist KPCC, KQED and CapRadio over the past year? Which asset manager forced local indie site L.A. Taco to furlough its staff and engage in an emergency membership drive? Which pension fund’s interests prevented philanthropists from supporting the Long Beach Post’s conversion from a for-profit to a non-profit newsroom, leading management to gut the staff? Which investment bank drove CalMatters and the Markup and Mother Jones and the Center for Investigative Reporting to engage in mergers to consolidate Californians’ news options? It wasn’t the evil Alden Global Capital that has cut 40% of the news staff at the Los Angeles Times since 2019; that was completely the doing of our civically interested local billionaire Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong, who has lost untold tens of millions of dollars investing in journalists with little hope of return on his investment. The reality is that if every asset manager who runs a California local news outlet disappeared tomorrow, the declining audience numbers and staff cuts across California newsrooms wouldn’t stop. The problem is sectoral, and the solutions should be sectoral.

California’s ambitious proposals to fund local journalism at scale

The California legislature is considering two potentially landmark pieces of journalism legislation that propose requiring Big Tech to fund local journalism. Although the mechanics differ significantly, the macroeconomic goal of both bills is to boost local news production by funding wage subsidies that make journalists’ labor cheaper for publishers to purchase without requiring those journalists to take a pay cut.

To accomplish this, Assemblymember Buffy Wicks’ AB 886 (the nominal target of CCIA’s ads) creates a mechanism for news publishers to take Google and Meta to third-party arbitration to argue how much the platforms owe news publishers for scraping the work of journalists, including for training their AI models. Alternatively, the platforms could opt to pay a fixed sum into a fund to avoid the uncertainty of arbitration. Publishers with more than five employees would then be required to spend at least 70% of those platform revenues on payroll, and most critically, would be required to publicly report those revenues so that the state’s journalism unions can ensure that the money goes where it’s intended. The bill is most similar to “bargaining code” laws previously passed in Canada and Australia.

Senator Steve Glazer has proposed his own framework, SB 1327, which hasn’t been mentioned in the ads, but which the state Senate recently passed with a bipartisan two-thirds majority vote. Glazer’s bill proposes to levy a “data-mining mitigation fee” on Google, Meta and Amazon for collecting the user data that powers the companies’ lucrative surveillance-based advertising services. The bill estimates it would raise $1 billion from the platforms annually, with about $500 million a year set aside for journalist employment tax credits for news employers, calculated as a percentage of those journalists’ wages. Another $400 million would be set aside for schools. On the pay-for side, the bill is most similar to Maryland’s digital advertising tax, and on the spending side, the journalist employment tax credits are similar to those recently passed (on a much smaller scale) in New York and Illinois.

Both AB 886 and SB 1327 propose content-neutral frameworks that would benefit publishers large and small, commercial and nonprofit, regardless of medium or editorial bent, to avoid violating the First Amendment or giving lawmakers discretion to corruptly punish publications they don’t like. Many journalism unions that represent local journalists across California, including mine, Media Guild of the West, strongly support both bills:

Big Tech’s pricey opposition

Big Tech hates this legislation, is spending heavily to kill it, and has been threatening to take local journalism hostage in California if the platforms don’t get their way. Last year, Meta threatened to ban journalism from its services — which include Facebook, Instagram, Threads and WhatsApp — in California if AB 886 becomes law, echoing a threat it has also made for the entire U.S. Google has now made its own threat of a news ban in California (after testifying that it wouldn’t) and has been testing removing news links from Google Search. Most the outside groups most noisily attacking AB 886 have Google as a major funder or member, including Chamber of Progress (a libertarian astroturf group), California Chamber of Commerce (which is funding Jeff Jarvis to fly in and lobby in opposition), and LION (which keeps invoking labor unions in its internal mobilizations against the bill, presumably leaving some LION members puzzled as to why broke local publishers are being told their interests are different from the interests of underpaid local journalists — I guess now is the time to disclose that it’s been your friends and neighbors at the Guild helping secure amendments to make the legislation friendlier to small newsrooms. We all live and work here, you guys). When the Computer & Communications Industry Association (members include Google and Meta) attacks “well connected” news companies in its new anti-AB 886 ads, it doesn’t do so out of envy: Google paid $1.2 million to the California Taxpayers Association to run scandalously misleading anti-AB 886 spots in 2023. This is distributed crisis PR for the powers that be, and the work appears well compensated.

An industry with this much power over local newsrooms is a threat to our journalistic independence, too much of which we’ve clearly already given away. California lawmakers would be wise to continue ignoring this corporate influence campaigns and keep focusing on making this legislation the best it can be.