Journalism after the death of hyperlinks

A case for the California Journalism Preservation Act.

It is well known among journalists who give advice to students that the things that worked for getting us into a newsroom won’t and maybe literally can’t work for them.

Circa 2011, after the mass journalism layoffs of the 2000s, one of the value propositions of being a recent journalism graduate is that I was cheap, energetic, optimistic, had paid for my own training and was willing to do anything, at a time when newsroom employers were interested in cheap, energetic, optimistic, already trained labor willing to do anything.

I arrived in a mainstream legacy newsroom that had already been gutted since its extraordinary staffing peak and landed a job on an institutionally prestigious desk, surrounded by Pulitzer-winning veterans, but doing blogging and aggregation to farm a truly astonishing amount of Google News traffic.

Naturally, I would like to think that I was especially talented and hard-working and totally deserved to be there; in retrospect, looking at how much experience I actually had and the work I was actually doing amidst the actually experienced and phenomenally talented journalists surrounding me, who were still doing traditional reporting and writing, the whole arrangement was also kind of insane. My eternal thanks still goes to every journalist of the Los Angeles Times who taught me the true craft and made me the journalist I am.

But one of the things that I did help bring to the newsroom, at the time, was a willingness to do more of my journalistic work on social media, especially Twitter.

Let’s just say that whole endeavor of helping haul a legacy newsroom into the digital era, from the perspective of a grunt newsroom member, was a huge pain in the ass. And I was a pain in the ass, too: Sometimes I tweeted things that were embarrassing to the company or myself, but also a lot of times I tweeted stuff that attracted a bit more attention to my work in a way that wasn’t happening on the home page or in the print edition. The print edition was in terminal decline, and so here was a new way of connecting our good work with audiences over new media.

Social media was a new thing, and it was hard for me and others to help bring the new thing into the world. Our bosses didn’t always really know exactly what to do with it or what the value proposition was. But here’s the thing: There may have been no value proposition whatsoever? Show me a newsroom that went all in on plumbing for audiences on social media between 2010 and 2020, and I’ll show you a newsroom that probably doesn’t exist anymore. I have 146,000 followers on the platform formerly known as Twitter and have a good laugh from time to time about how meaningless that number is.

The problem I have in talking to journalism students today about how to break into journalism is that not only are a lot of legacy newsrooms still in a long freefall; so are a lot of the most interesting digital, nonprofit, anti-“view from nowhere” community-oriented outlets and media that were supposed to rise up in their place. (Go start a podcast and try to find some sponsors and tell me how it goes.)

Maybe all these outlets did a bad job hiring their business-side people or can’t stop making bad editorial decisions that audiences didn’t like or are too biased toward one political faction or something. Maybe it’s an international conspiracy to do bad journalism, because there seem to be a lot of the bad people making bad decisions causing news outlets in other countries to collapse badly, too. We need our top media scholars to study how almost everybody, almost everywhere is somehow doing a bad job at journalism and refuses to adapt to the internet and is also getting worse at making decisions all at the same time.

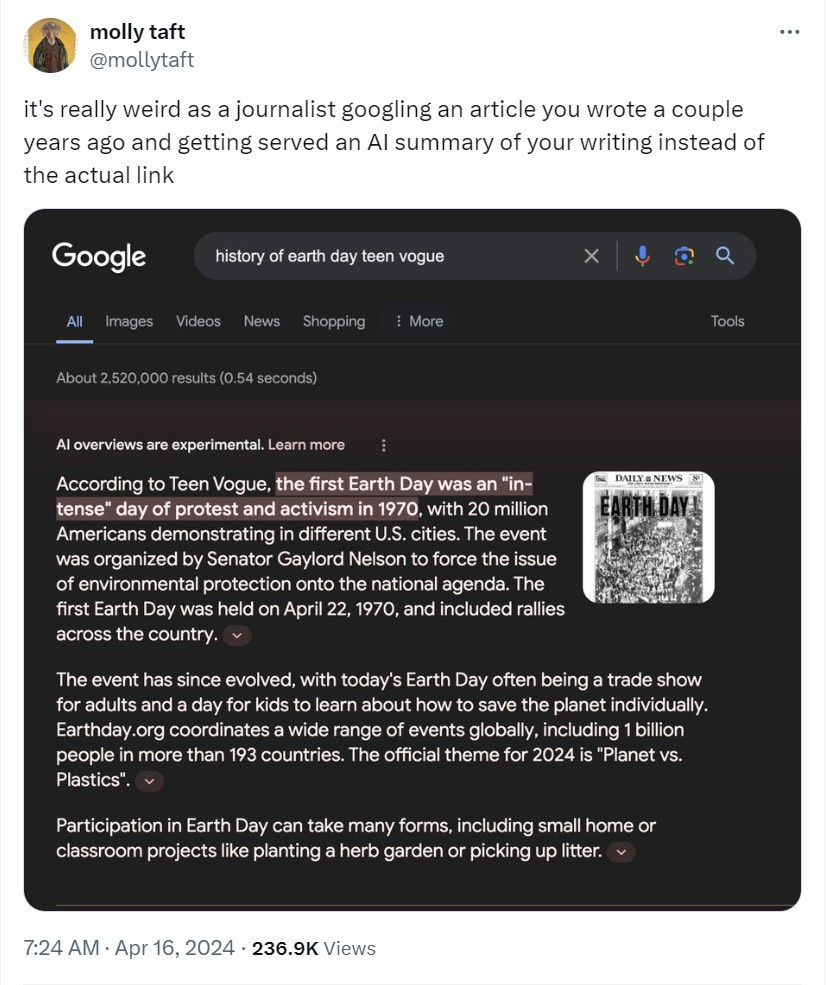

Just one more thing: I have a different idea about what’s happening to all of us, which is the long death of the hyperlink-based internet, which I wrote about in the San Francisco Chronicle yesterday:

For much of the past two decades, Google and news publishers have operated on an implicit bargain; outlets like the Chronicle or the Los Angeles Times, where I was a longtime reporter, would allow Google to crawl and feature my stories on its services. In exchange, Google would send these publishers a river of users via hyperlinks.

The understanding was that users who no longer subscribe to print newspapers would look at digital ads on news websites or buy digital subscriptions. In return, those users would presumably continue using Google (itself a profitable seller of digital advertising) as their preferred portal to find high-quality information from a variety of sources.

…

Anybody hoping to shore up Google’s still-significant referral traffic to publishers — or anyone who’s propagandizing that the idea of paying journalists is tantamount to a “link tax” (the government never touches Google’s money) — is fighting yesterday’s war. The old internet where users actively hunt for information and prowl from site to site is dying.

Following hyperlinks in search of accurate information is annoying, inefficient and increasingly filled with scammy clutter. On the fenced-in internet of tomorrow, AI-powered portals controlled by a small handful of powerful international companies will treat us like stationary consumers who passively expect knowledge and content to come to us, not the other way around.

Think of the uncanny algorithms of TikTok’s For You Page, OpenAI’s general purpose GPT chat interfaces or Elon Musk’s (not exactly successful but persistent) quest to transform the once hyperlink-friendly Twitter into X, an “everything app” where users “can do payments, messages, video, calling, whatever you’d like.”

The dream of the open internet is fading and being replaced by a surveillance-driven dystopia powered by free and low-paid labor. The California Journalism Preservation Act is just the first of many bills that will be necessary to point out that this content-creation arrangement is unsustainable for workers — and also everyone else.

The fundamental reality of the digital experience, the basic fact that we must come to grips with in making 21st century media policy, is that there is far too much information and too much content out there for users to go find what they really need. The major problem and digital infrastructure project of the tech industry on the content front is to figure out how to automate the synthesis and delivery of that information into something that isn’t a huge pain in the ass for users to go looking for.

But what that means is that the hyperlink, which used to be a handshake, a friendly act of cashless barter across the open web, is now the primary means of information-highway robbery. When you reach in for the shake, Google’s hand is already gripping a gun:

Everybody is going to argue about the copyright implications of all this until they’re blue in the face, with varying levels of sincerity or corruption (and I swear to god, you’ll need to ask the people involved in these arguments who they’re getting money from, and how much).

But I am going to say something that I mean sort seriously but not literally: I don’t really care about copyright! I don’t really care about paywalls! I’m okay with it if you only ever see my reporting via a chatbot! Copyright and paywalls are simply means to an end, and that end is the pursuit of human knowledge and self-liberation: the end is our freedom. And one of the principles of human freedom that I hold dear to my heart is that nobody should be providing labor to massively profitable corporations for free.

The fundamental media problem of the A.I.-driven future isn’t intellectual property; the fundamental media problem of the A.I.-driven future is work. Journalism as an action, not a product.

I recently had a encounter with AI of the worst kind. I wanted to send a link to a New York statute. Google brought up a site that I have used before. I clicked.

And what I got was NOT the page with the statute. I got an AI summary of the statute. Thank you browser. It wasn't anything that had a link I could copy and paste.

I had to go to the website that actually has the statutes and then search IT for the statute I wanted. Luckily THAT brought me up the actual link that I could copy and paste.

"The print edition was in terminal decline, and so here was a new way of connecting our good work with audiences over new media.”

I’m all in favour of what happened, in terms of expanding into the digital world. But I don’t understand why so many brilliant people in the news industry say print is in terminal decline.

It may be a luxury, but there’s still an appetite for it. These days, I work with a lot of people on books, and nobody wants to publish without some kind of print version. Why should news media be different?

Really, I’m baffled. It’s like news organisations WANT print to disappear.