Journalism's fight for survival in a postliterate democracy

The truth is going out of business as technology turns us into a folk-story society, ripe for influence by a demagogue.

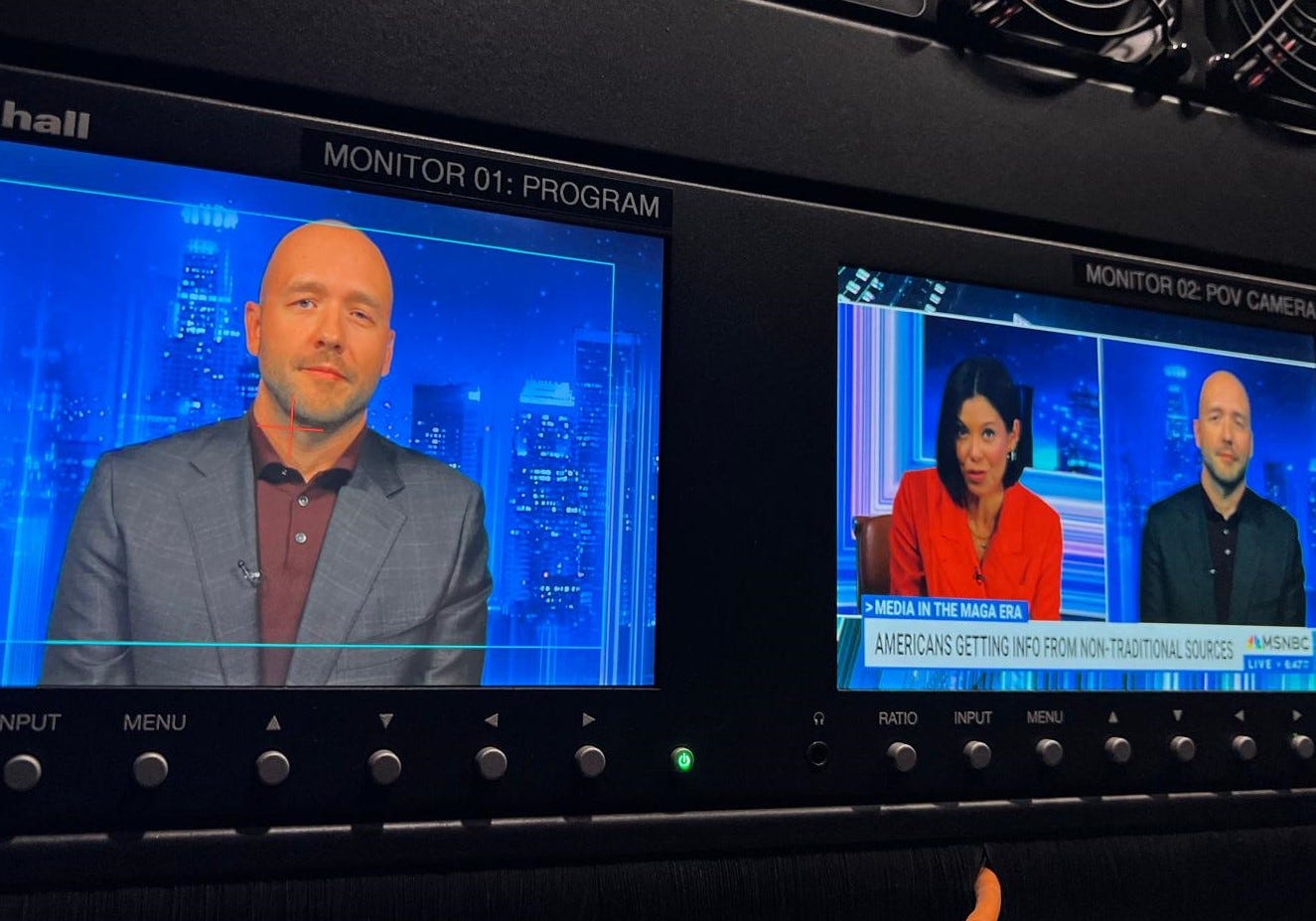

On Friday night, after I appeared on Alex Wagner’s MSNBC show to talk about my essay “Lessons on media policy at the slaughter-bench of history,” the number of subscribers to this newsletter exploded and nearly doubled overnight.

I haven’t monetized my writing here, but I wanted to thank the many of you who pledged money anyway in case I ever do. This newsletter has been a scratchpad for my obsessions in a time of trouble, and I’m grateful and not a little humbled that some of it has resonated.

I wanted to elaborate some more on Alex’s question from the interview about what I meant when I said we live in an increasingly postliterate media economy. It’s a regime in which the truth is going out of business for macroeconomic reasons, not because a few editors picked some bad stories and headlines:

The work of obtaining facts has a major economic disadvantage against the production of bullshit, and it’s only getting worse. I’m a pro-labor person, so I often think about the problems of our journalism through a lens of how we do our work, why it’s done, and who’s paying for it. After many years of watching my fellow journalists suffer at legacy newspapers, digital startups, big commercial newsrooms, small nonprofit outlets and public media all alike, here’s what I learned the hard way: America’s marketplace of ideas has a competition problem. The biggest story about media and the internet is that new technology — AI, social media, smartphones, etc. — keeps driving down the cost of producing bullshit while the cost of obtaining quality information only goes up. It’s getting more and more expensive to produce the good stuff, and the good stuff has to compete against more and more trash once it’s out on the market.

For example: For all our advances in information technology, the journalistic work of breaking a truly important story often doesn’t look all that different from 50 years ago. Driving to sources’ houses to knock on their doors, fighting government agencies over fulfilling public-records requests, cold-calling 1,000 potential sources — this work is not getting much more efficient to produce. Worse, the journalist who walks out the door to provide some actually new information to the world is meanwhile not more “productively” spending their time at their desk grinding out short, low-protein, lower-effort content to build their online audience, which is a volume game.

This economic problem of quality news production — where the really good stuff only gets more expensive because technology can’t make it more efficient — is called Baumol’s cost disease. It’s the same reason your local symphony orchestra, if you still have one, is reliant on philanthropy, corporate sponsorships, or hiking ticket prices for an inevitably more elite audience whose own wealth has been increasing from productivity increases in other parts of the economy. For journalists, when your job is to bring the facts to the biggest audience possible — when we’re already trying to climb out of a hole of historically serving affluent/whiter audiences — this dynamic is toxic. Baumol’s cost disease also the same principle why shifting newsrooms to be nonprofit rather than for-profit is not going to fix the underlying economic issues making quality journalism harder to fund.

Consumers have gotten pretty tolerant of bullshit. By “bullshit” I’m referring broadly to the kind of stuff — like social media commentary, podcast chat shows or ChatGPT summaries — that can contain factual information but often contains nonsense, in a context where there’s zero consequences for bullshitting to begin with and then bullshitting even more. Consumers hardly ever realize it, but they hold traditional news media to vastly higher standards of accurate and ethical behavior than practically every other information source they encounter, even when they’ve started relying on those other information sources instead of the news media. It’s good consumers hold journalism to high standards. The problem here is that the bar is getting lowered, not raised, for everything else.

Written journalism has long played an important flywheel role in how information gets distributed to consumers and voters, but fewer people are getting and reading the written stuff, and platforms are making the written harder to monetize. I am an ardent media pluralist and hold a holistic view of how informing the public actually works in real life, where written journalism plays an important feeder role despite most people never encountering the original articles in the newspaper or ProPublica or wherever. Someone, somewhere, puts in the work of finding original facts, distributes them to a smallish crowd of news junkies and nerds who subscribe directly or are looking for something specific on Google, and then a flywheel effect kicks in: the good stuff then gets filtered out into a far larger ecosystem of social media, TV, radio, bloggers, influencers, dinner tables, coffee shops, city councils, state lawmakers, think tanks, FBI agents, etc. For example, if you’re only reading this because you saw me yapping on MSNBC, that happened because a producer read my last essay, which Alex then talked about on the air, all of which led some other content creators to talk about the issue and my piece, etc. But one of the poorly understood infrastructural changes happening to this ecosystem in recent years is that our trillion-dollar platforms have grown increasingly hostile to distributing writing, either by driving news off their services, degrading hyperlinking, shifting to AI-plagiarized summaries, and relying more on user-generated content. Time you spend reading a magazine article is time you’re not spending on Meta products looking at digital ads and making Mark Zuckerberg richer. The flywheel is breaking. (I won’t even get into the digital advertising monopoly issue here, which has been inflation-biting consumers without you even realizing it: Buying a $5/mo subscription to a Substacker is cool, but in legacy media, you used to get way more journalists for your dollar.)

Consumer preferences and capabilities are also taking a turn for the worse: If you are a Millennial or older and haven’t done this already, ask some of your teacher friends how it’s going with their students’ ability to spend time with books or to write without the assistance of ChatGPT. A tidal wave is coming. The destruction of patience is one of the most dramatic cultural shifts we’ll probably experience of our lifetimes, and it pervades everything — journalism, music, comedy, the works. I was at a dinner party recently with a film studies professor who said some of her own students didn’t really watch movies anymore. I don’t say this to beat up on Zoomers or act like it’s a generationally localized phenomenon: I’ve been watching a lot fewer movies and spending a lot more time on TikTok too. I just think the kids shifted their media habits first and the rest of us are slowly catching up. “Ten years ago, more or less, I realized that I had forgotten how to read,” one of my journalist colleagues, Vincent Bevins, wrote recently about training himself to have the patience for books again. “I never pretend that I am going to get some reading done with a cellular device on my person. Those people that arrive at a coffee shop, and then place a phone and a book together on the table, are trying to beat Satan in a game that he has devised. It might be possible to win, but I have never seen it done.”

The result of all of this is a growing consumer alienation from the actual sources of information, a return to a kind of folk-story society ripe for manipulation by demagogues who promise simplicity in an increasingly complex world. The way we talk about the media and political coverage — as a matter of editors and producers picking stories and headlines — is stuck in the 20th century. It’s comfortable and familiar to complain about the billion-dollar media companies that often annoy us but not the trillion-dollar platforms deciding what information hundreds of millions of Americans see. This is why I think anyone pointing toward the hedge fund-ification as the primary force killing local news (though they are, also, killing local newsrooms) is mistaking a Wall Street symptom for a far vaster macroeconomic disease.

I don’t say all this to be depressing or to create a sense of hopelessness. I am not a pessimist. To fix a problem, you first have to understand it, and the problems here just happen to be significant — requiring not just policy intervention, subsidy, and breaking up a few trillion-dollar tech companies, but also a social will toward truth.

There have been times before when Americans have confronted forces of alienation, fragmentation and plutocratic control — but the work starts with us and the will to change, and nowhere else. Here is where I turn to the young and idealistic Walter Lippmann of the Progressive Era:

Yet we have to face the fact in America that what thwarts the growth of our civilization is not the uncanny, malicious contrivance of the plutocracy, but the faltering method, the distracted soul, and the murky vision of what we call grandiloquently the will of the people. If we flounder it is not because the old order is strong, but because the new one is weak. Democracy is more than the absence of czars, more than freedom, more than equal opportunity. It is a way of life, a use of freedom, an embrace of opportunity. For republics do not come in when kings go out, the defeat of a propertied class is not followed by a cooperative commonwealth, the emancipation of woman is more than a struggle for rights. A servile community will have a master, if not a monarch, then a landlord or a boss, and no legal device will save it. A nation of uncritical drifters can change only the form of tyranny, for like Christian's sword, democracy is a weapon in the hands of those who have the courage and the skill to wield it; in all others it is a rusty piece of junk.

I’m a concerned global citizen in Canada who tries to do deep dives on world issue causes/solutions that impact a sustainable, just economy. The media landscape/accessibility of factual and insightful information came into sharp focus to me prior to our 2015 election when Postmedia purchased 300 Canadian media properties. Journalists slashed, more paid editorial “comment” passing as reporting and no progressive voice left in MSM primarily hedge fund/Conservative owned landscape. New journalistic properties necessarily requiring paywalls that a fact starved public increasingly can’t afford (due to decrease in disposable income that Conservative/inflationary policies effect).

So, meeting people “where they are” now requires journalists to move into evolving technical platforms…that has led this old lady into having to expand my search to find published and podcast material on Substack, Bluesky and Threads.

There will be a lot of older voters who will stay in silos and fail to keep up…and there will be many low information voters who cannot afford time/money to find out …what they don’t know (and how to stave off propaganda). The autocrat/oligarch messengers will be well funded to continually confuse us and buy policy that makes it harder to amplify and descern truth.

Glad I stumbled on your writing.

Funny how I've been sitting on a Naomi Klein book for like 3 months now. Distraction is a new way of life and getting news updates on my phone occupy way too much time. The distraction is constant throughout the day. No wonder so many younger folks have no clarity on real issues and what political policy actually means. I am more pessimistic now (could be an age thing since I'm 65). I don't know how we can maintain or regain Democracy in this current state of misinformation. It might be impossible.